02 Oct TALL TALES: EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW, TIMOTHY EGAN

Editor’s note: Telluride Inside… and Out’s monthly column, Tall Tales, is so named because contributor Mark Stevens is one long drink of water. He is also long on talent. Mark is the author of “Antler Dust” and “Buried by the Roan,” both on the shelves of Telluride’s own Between the Covers Bookstore, 224 West Colorado Ave, Box 2129. He is also a former reporter (Denver Post, Christian Science Monitor, Rocky Mountain News) and television producer (MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour) now working in public relations. The following blog is a major coup: an interview with Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist Timothy Egan on his latest great book on Edward Curtis.

On Tuesday, Oct. 9, Edward Curtis gets his due.

That’s the date when New York Times’ Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist Timothy Egan—one of the best thinkers and writers about today’s American West—publishes “Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher, The Epic Life and Immortal Photographs of Edward Curtis.”

This gorgeous book, chock full of classic Curtis images, completes an early Twentieth-Century (sort-of) trilogy for Egan.

Egan won the National Book Award for “The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American Dust Bowl” and more recently published “The Big Burn: Teddy Roosevelt and the Fire that Saved America,” a frightening and cautionary tale about the kinds of wildfires we can expect in the American West sometime very soon.

“Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher” offers another wonderful dose of Egan’s compelling narrative style a mountain of detail about the epic life of one of the Twentieth Century’s most overlooked photographers and anthropologists.

Egan was kind enough to answer a few questions about Short Nights exclusively for Telluride Inside…Out.

(A review of the book follows, below.)

Question: Clearly Edward Curtis’ photographs—along with the recordings and other cultural records he produced—constitute one of the most significant anthropological works ever undertaken. That alone seems reason enough to write a book about Curtis, but what specifically drew you to the idea of investing your time in his story today?

Egan: I loved his journey, his arc as an artist — this amazing story of a sixth-grade dropout who takes on one of the most grueling photographic projects in history. There is so much inherent drama just in getting to these places and convincing the people to pose for him and then trying to understand their cultures. Imagine if a single person took on all the nations of Europe.

Question: When did you first learn about Curtis and what he had accomplished?

Egan: I live in Seattle, where Curtis blossomed. He’s everywhere, but he’s one of those treasures hiding in plain sight. It was only when I bothered to look into his life story that I realized there was a compelling narrative here — about him, about the collision of many nations.

Question: Do you think Curtis’ lack of formal, higher education caused others to take him less seriously during his lifetime?

Egan: Yes. Curtis was shunned, dissed, ignored by the elite — and this only spurred him on further. At the Smithsonian, he was so upset when their resident Indian “experts” told him the Apache, and most tribes for that matter, had no religion. His knowledge came from first-hand observation and the journalistic tasks of asking multiple questions. He was driven by a determination to prove that most of what Americans thought they knew about Indians was wrong.

Question: Would Curtis’ analysis of the “Custer Conundrum” have been taken more seriously if he had academic credentials—or was he up against politics from the outset?

Egan: Great question. Curtis basically solved the true story of what happened to Custer well ahead of anyone else — again, because he asked all the right questions, of those involved, on both sides. But I think he was ignored, or shunned, because America wasn’t ready yet to hear that the hero Custer was a fool, and worse. Custer’s widow fought Curtis and used all her influential friends to discourage him from publishing his findings. I read those findings in a bound volume at the Library of Congress — a century after he wrote them up and buried them, and he nailed the story. Too bad he didn’t get credit for it at the time.

Question: Do you think Curtis’ belief that American Indian was “massively misunderstood” holds a lesson for our foreign or domestic policy today? For how Indians continue to be treated and viewed today?

Egan: Yes there’s a larger lesson in the Curtis epic: some things are not as they seem. If you look behind the stereotype, as Curtis did, and try to find the humanity in subjects written off, you can often find something very enlightening.

Question: Curtis comes across as fairly matter-of-fact about all the physical challenges, including several times when he risked his life, and much more focused on getting his message across. Is that a fair assessment?

Egan: Yes, that’s accurate, I think. He was a tough son of a bitch, very nimble and athletic until he lost his health, and not afraid of much. I think that’s because early on — on Mount Rainier, on the Alaska Expedition — he took crazy physical risks and always survived them. This gave him a confidence, perhaps foolish, that nothing could touch him.

Question: You’ve visited all the same locations where Curtis took photographs—can we really understand today the sheer effort it must have taken to complete the life work that Curtis set out to achieve?

Egan: No. I travelled by plane and car, with a notebook and an iPhone (with a great camera). Curtis travelled by train, wagon, horse, and schlepped around hundreds of pounds — of glass plate negatives, notebooks, his wax cylinder audio recordings, source books, maps, plus food, bedrolls, tents, kitchenware etc.

Question: Have you had a chance to page through all 20 volumes of “North American Indian?”

Egan: I have, and what an experience. You put on white gloves, while someone looks over your shoulder, and see these magnificent images come to life. It’s very moving for someone who loves books. And rare — remember, there are less than 300 complete sets in existence.

Question: Three of your books—”The Big Burn,” “The Worst Hard Times” and now “Short Nights”—focus on the early decades of the Twentieth Century. Is there something specific that draws you to write about this era?

Egan: Curious. I never planned it this way. But I guess once you start hanging out with Teddy Roosevelt and all these characters at the dawn of the Twentieth Century—the so-called American Century—it’s tough to shake them.

REVIEW:

“The largest anthropological enterprise ever undertaken?”

That’s Mick Gidley, a professor of American literature, as quoted by Timothy Egan near the end of this exhaustive, gripping look at the life of photographer Edward Curtis.

M. Scott Momaday, who won a Pulitzer Prize for his novel “House Made of Dawn,” lauded Curtis for capturing the Indians of North America “so close to the origins of their humanity, their sense of themselves in the world…”

Egan’s “Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher, The Epic Life and Immortal Photographs of Edward Curtis,” makes a clear case that the accolades are justified.

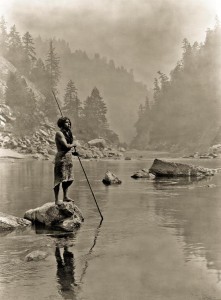

You will recognize many if the iconic pictures Curtis captured. “Woman and Child,” 1927. “Geronimo—Apache,” 1905. Many more. And perhaps, like me, you never stopped to think too long about the work required to produce them. “Short Nights” fills the gap.

In “Short Nights,” Egan traces Curtis from his first picture in Seattle (1896), when he was no crusader for Indian rights.

“Curtis wanted pictures. Indians their treaty rights, political autonomy and property disputes—all of that was somebody else’s fight. Politics. Injustice. Blah, blah, blah. Who cares? The exchange between photographer and subject was purely a business proposition…”

But that view doesn’t last long.

Curtis’ empathy grows as he finds his way inside a variety of Indian cultures. In the end, Curtis took 40,000 photographs, recorded 10,000 songs, captured vocabulary and pronunciation guides for 75 languages and a documented an “incalculable number of myths, rituals and religious stories from deep oral histories.”

“Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher” is a terrific biography of Curtis that weaves in and out of the fabric of U.S. history and will make you wonder what kind of country we would have created had early settlers and Native Americans found a way to co-exist, or if just a slice of Curtis’ open-mindedness governed the interactions from the outset.

Curtis’ determination to document the Native American cultures before they slipped into the void of history is, quite simply, off the charts.

“I want to make them live forever,” he said. “It’s such a big dream I can’t see it all, so many tribes to visit.”

Egan tracks Curtis back and forth across the country, to the American Southwest and the Pacific Northwest and the High Plains and Oklahoma and everywhere Native Americans called home, even if their “homes” had been drastically altered in their losing negotiations with the European settlers.

“After a year’s absence, Curtis noticed that natives of the Southwest had changed Government agents who had banned even more ceremonies. As in Montana, children were hauled off to boarding schools run by the missions, where their spiritual lives were handed over to another God. The boys were supposed to learn how to farm and read, the girls how to be homemakers and serve tea. Those who resisted were threatened with a loss of provisions and derided as ‘blanket Indians.’”

Curtis comes across as fanatical, restless, eager and endlessly unsatisfied with his work.

“After several weeks, he was allowed to follow Apache women as they harvested mescal, roasted it in a pit and mixed it for a drink. Still, he was only scratching the surface—an embedded tourist. He wanted detail, detail, and more detail. He heard whispered talk about a painted animal skin, a chart of some kind that was the key to understanding Apache spiritual practices. Curtis offered a medicine man $100—a fortune, more than any person on the reservation could earn in a year—if he would show him the skin and explain what the symbols meant. His bribe was rejected.”

Curtis’ fame grows. He struggles to get close—and disappear within—various tribes. He descends a Hopi ladder into a Kiva “thick with rattlesnakes.” He seeks financing through the powerful J.P. Morgan and struggles for decades to meet the schedule and obligations that Morgan funded. Curtis analyzes the site of Custer’s Last Stand and, together with his interviews with Native Americans, draws a controversial conclusion that Custer “had unnecessarily sacrificed the lives of his soldiers to further his personal end,” drawing scorn from President Roosevelt and others.

In one of the most moving chapters, Egan details Curtis’ relationship with Alexander Upshaw, a Crow from Montana who had been raised in a boarding school in Pennsylvania and who became Curtis’ most valuable interpreter—a “fixer” in today’s media lingo—who smoothed the way for Curtis as he approached new societies.

“Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher” has heft, detail and history but also rides lightly on Egan’s magical narrative touch. The reading is a breeze; the details powerful. It’s easy to spot the places where it might have been easy for Curtis to chart a different and perhaps more satisfying course, but Egan makes it clear that Curtis’ agenda and zeal were at a level of intensity that overshadowed normal self-analysis.

Egan:

“His theme, consistent from the beginning, was that Indians were spiritual, adaptive people with complex societies. They had been massively misunderstood from the start of their encounters with European settlers, and they were passing away before the eyes of a generation, mostly through no fault of their own. For them, the present was all of decline, the future practically nonexistent, the past glorious.”

Susan Sontag once said that photographs “alter and enlarge our notions of what is worth looking at and what we have a right to observe.”

Curtis spent his life opening the eyes of those who preferred to look away or ignore what was happening to the Indians. Egan, in turn, finds mountains of humanity in the life of Edward Curtis and opens our eyes to a man who worked to “enlarge our notions” through photography and ethnography and change the way we treated our fellow human beings.

Pingback:Q & A With Timothy Egan – “Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher” | Don't Need A Diagram

Posted at 05:17h, 09 October[…] (The following post was first published by Telluride Inside … and Out.) […]

Pingback:What Would Molly Ivins Think? | Don't Need A Diagram

Posted at 13:01h, 20 October[…] (The following post is a longer version of a piece first published by Telluride Inside … and Out.) […]