07 Oct In Telluride’s Backyard: Exploring the Four Corners

Those who don’t know history are destined to repeat it, Edmund Burke.

Here’s the dirt on dirt.

Dirt (or soil) isn’t just a mix of clay, sand and humus that lies over bedrock.

It isn’t simply dust, grime or filth either.

For archaeologists Mark Varien and Ricky Lightfoot, dirt—or the layers of sediment they call “stratigraphy”— is often a blanket covering thousands of years of history.

Telltale signs and clues: pottery sherds; chips of stone discarded when one of our an ancestors made a stone tool; two different colors of earth, a red band ringing a gray deposit suggesting, what?, a post hole perhaps; a trace of a substance that does not belong where it was found, such as the sandstone we spotted on one site location, discovered on top of a mesa where an ancestral Pueblo family undoubtedly used it to build their home.

Mark and Ricky, Top Dog diggers of dirt, were trip leaders and head scholars on the recent Crow Canyon Archaeological Center trip we took to do some exploring in our own backyard: the ancestral Pueblo Indian ruins sites of the Four Corners region. It was a six-day outing that offered insights into the major features of the deep human history of Pueblo people that spanning the last four centuries.

The dynamic duo were the teachers everyone would have wanted for home room: passionate about their subject – essentially, understanding human history and socio-cultural evolution – wise, witty and empathic. And it was Mark and Ricky who set the tone for what turned out to be an unforgettable, eyes-wide-open adventure.

Although, truth be told, we went for the adventure – but stayed for the people.

Our Crow Canyon trip, like the discipline underlying it, archaeology, came down to people more than places and things: the ones we shared discoveries with and the ones who came before.

“I chose archaeology as my life’s work because it is the social science that takes as its subject matter all cultures that have occupied our planet throughout the entire span of the time we have been here,”explained Mark.“As such, it provides the most complete understanding of our collective humanity. About 2 percent of human history has taken place since the advent of writing. Archaeology is the key to learning about the other 98 percent.”

Our fellow travelers, a delightful and ultimately fully integrated, supportive group, included a BFF from Telluride, a book author; a financial analyst/advisor/entrepreneur and Crow Canyon board member; a retired Emmy Award-winning director and his partner, a former executive in the food industry and expert chef; and a rocket scientist.

The peerless team of Crow Canyon’s explorations coordinator, David Boyle, and development officer, Kimberly Karn, were in charge of logistics, soup to nuts – served up on a silver platter. Also herding cats. Over the short week, they proved to be unflappable models of quiet efficiency.

Then there was archaeologist, educator and artist Rebecca Hammond.

Becky is member of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, clearly and passionately plugged into the past and present energy system of her culture. As such, she is a fierce protector of American Indian customs within the context of archaeological inquiry and interpretation. Becky, who has worked at Crow Canyon for 15 years and serves on Crow Canyon’s Native American Advisory Group, is also one mean spear-thrower – her weapon of choice: an atlatl – and she has a rapier wit to match. Cross her at your own peril.

With Becky in the lead, cracking jokes and delivering invaluable insights with an ALL CAPs urgency, on Day 2 our group ventured deep into the Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Park, a vast and remote area of canyons and mesas located southwest of Mesa Verde National Park, where we scampered – ok, not scampered so much as stepped with great caution, some of us hearts in throat – up and down ladders to explore cliff dwellings, residences and public spaces engineered into natural rock shelters in steep canyon walls dating back roughly to A.D. 1200s, the “classic” period for the Mesa Verde region.

And that’s where we almost got stuck.

In an interview I did years ago for Mountainfilm in Telluride, travel writer Tim Cahill quipped:“There is no story unless something goes wrong.”

Our misadventure began when the rains, in the forecast for days, held off in the morning, but came with a vengeance that afternoon while we were exploring a second cliff dwelling.

Roads on the res are nearly impassible under the best of circumstances (read, bone dry). Following a downpour, fagettaboutit: they turn slick as a luge run and include washboard jarring.

There we were in the middle of nowhere, with little food and drink and no amenities in sight. No shelter whatsoever should we be stranded overnight.

Not a pretty picture for a trip that was more or less billed as a glamping expedition.

In the end, Ricky and David, working way above their pay grade, soldiered our two vans through the muck and slick, shimmy-shaking, jack-knifing and sliding their way to a gravel road and safety.

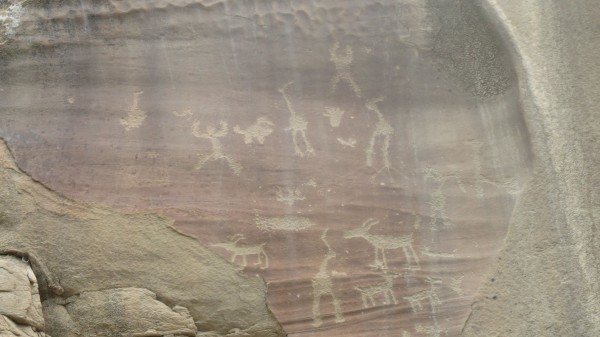

Next stop, Kiva Point, to investigate a wall of rock art or petroglyphs: In pictogram-speak, we learned that a figure with arms up in the shape of a goal post is not pleading “Don’t shoot.” It is invoking rain. And trapezoidal humanoids with antennae-like shapes emerging from their heads like a headdress do not represent friends from outer space. The forms are associated with the Basketmaker II period, 500 B.C. – 500 A.D., the era that twins with corn and marks the shift from hunter-gatherers to farmers, one of the most significant, if not the most significant shift in human history.

More dirt on our trip.

We decided to sign up for the Crow Canyon trip because we have always known the Four Corners region was rich with ancient sites – per Mark Varien, literally hundreds of thousands of archaeological sites or about 100 sites per square mile in some areas – making our extended backyard (SW Colorado, Utah and New Mexico) the region with the greatest density of archaeological wonders in America, on par with and in some ways surpassing other areas around the globe with renowned monuments to history, the pyramids of Egypt being just one example. Yet, when Clint and I traveled, it has always been to far away places in Asia, Europe or South America. We were long overdue to correct that oversight.

“The Four Corners is paramount in our ability to understand the human experience because of the vast number of archaeological sites, their incredible preservation because of our arid climate and the fact that some are located in completely dry caves enabling the preservation of otherwise perishable materials, the fact that we have a technique—tree-ring analysis—that allows us to date sites with a greater precision than anywhere else in the world,” continued Mark. “And those same tree rings allow us to reconstruct the past climate with a greater precision than anywhere else in the world. Finally, and perhaps most important, we have a connection between the ancient sites we study and living American Indian cultures. That simple fact allows us to integrate archaeological knowledge with the oral traditions of these living people to create a more inclusive story of the past, one that examines both the material and ideational realms. This simply is not possible in most other parts of the world.”

Sites in the Four Corners span the time from the arrival of the first Americans over 13,000 years ago to modern Anglo settlers. But the vast majority date from the Pueblo Indian culture to about 1,000 years ago.

“Probably the central characteristic of Pueblo culture is their commitment to corn farming as the basis of their economy. For the Pueblo culture, corn farming is much more than a mode of subsistence; it permeates every aspect of their lives, including religion and how they understand their place in the universe,” explained Mark. “There are also artifacts that typify Pueblo culture, most importantly their architecture and pottery. The Pueblo style of building influences the Spanish, who were the first European settlers in the region and it continues to influence our building styles even today.”

Our robust itinerary included visits to Chaco Canyon and the multi-storied “great house” at Pueblo Bonito; the great kiva in Aztec National Monument; cliff dwellings and rock art on the aforementioned Ute Mountain Ute reservation; a day floating the (very muddy from the deluge the day before) San Juan River past more than 300 million years of geologic strata and indigenous desert big horn sheep, with stops to view the spectacular panels of rock art and a remarkable cliff dwelling called River House; a visit to Castlerock (near Cortez), where Ricky guided us around the site he excavated in the early 1990s for insights into warfare and violence that occurred during the final years of the Puebloan occupation of the Mesa Verde region.

On the last full day of the adventure, we visited the Indian Camp Ranch, where Crow Canyon has begun a new multi-year research project exploring the earliest Pueblo communities that developed in central Mesa Verde region in during the 7th century. The goal of the so-called Dillard Site project is to answer a few basic questions: When did Pueblo people first colonize the region? Where did these early farmers come from? How did these ancestral Pueblo families organize themselves into larger communities first form in the region? What was the nature of the community that surrounded and included the site?

Truth be told, the underlying goal of our Crow Canyon adventure was the joy of finding answers to those and other basic questions about the region and developing an understanding of the deep history of the American Indian cultures that lived there: Pueblo, Ute and Navajo. And based on what we learned, to ask what all that teaches us about the development of human societies everywhere and who we are today.

“We examined the origins of Pueblo, Navajo, and Ute culture and visited sites and Native people that showed us how those cultures changed over time. We saw how the art created by the first Pueblo Indian farmers in the region can teach us about the ideas that were important to these first farmers,” concluded Mark. ”We also saw how these beginnings led to the creation of a Pueblo society that grew in numbers and how, as the population size increased, how at their social and political and economic organization also developed. That was perhaps most apparent on our visit to Chaco Canyon, where we saw the great houses and public buildings created by Pueblo society between about A.D. 860 and 1150, buildings that served as the ceremonial and political center for the larger Pueblo world, facilitating the exchange of economic goods throughout the region. We also learned that Pueblo society had to cope with an ever-changing environment and that coping with constant change led to transformation in the society itself. That was exemplified by our visit to the backcountry cliff dwellings on the Ute Mountain Ute lands, where we learned about the forces that led to Pueblo people migrating out of the Four Corners region leaving it entirely depopulated by about A.D. 1300. Finally, we learned about the resiliency of Pueblo culture and how it has met all of these challenges and continues to thrive today in 21 separate nations located in New Mexico and Arizona.”

How often have you traveled the highways and by-ways of Southwest Colorado, Utah and New Mexico and noticed the scenery? Ok, so you looked, but did you really see the wonders your surroundings held? And if by chance you saw, did you ever perceive what was hidden beneath the surfaces? Cue scholars and educators like Mark, Ricky and Becky, who also told us the single most important factor in learning is emotional engagement or exactly what their stories elicited in our band.

The trip was the ultimate show and tell, a glimpse into a rear view mirror spit-polished by scholars for a deeper understanding of the present in order to better navigate the road ahead.

Our Crow Canyon adventure was not about what we found. It was about what we found out.

About Crow Canyon:

Crow Canyon Archaeological Center is located in southwestern Colorado just outside of Cortez, a rewarding day trip from Telluride of a little over two hours each way.

For 32 years, the on-campus staff has made its business to study and teach human history, particularly the rich history of the ancestral Pueblo Indians (aka, the Anasazi), who inhabited the canyons and mesas of the Mesa Verde region hundreds of years ago.

Crow Canyon may be regional, but its vision is global: “To expand the sphere in which we operate, both geographically and intellectually, and show how the knowledge gained through archaeology can help build a healthier society.” And the Center walks its talk: all of its award-winning programs are developed in consultation with American Indians, enhancing the archaeological perspective of scholars with a cross-cultural perspective.

Crow Canyon’s earliest beginnings have two threads: one is Ed and Jo Berger who operated the Crow Canyon School outside of Cortez, Colorado, where they brought high school students from Denver to do a wide range of outdoor, experiential education. The other is an anthropology professor from Northwestern University named Stuart Struever, who, in 1968, founded the Center for American Archaeology in Illinois, which was a pioneering attempt at creating a long-term, multidisciplinary archaeological institute that was privately funded and that conducted its research by involving the public—adults and school children—in both archaeological excavations and in laboratory analysis of the artifacts recovered from those excavations. In 1982, Stuart took a sabbatical in Telluride in order to plan a new branch campus of the Center for American Archaeology (CAA). He met the Bergers and convinced the Board at CAA to purchase the Cortez campus from the Bergers, send the Bergers to Illinois to learn the CAA curriculum, and build a lodge on the new Cortez campus. The branch campus of CAA opened its doors for research and education programs in 1983, but that only lasted about a year. The Bergers and Stuart realized they had a different vision for what the institution could be, and CAA realized they could not fund a branch campus. fledgling institution needed greater financial support, Sso Stuart asked his friend from childhood, Raymond Duncan, a successful Denver businessman, if he would be the Chair of the Board and help fund a new, independent archaeological center, and Ray said he would if Stuart would quit his job as a tenured professor at Northwestern and become the full-time president of the organization. Stuart did, and the Crow Canyon Archaeological Center was formed.

“The Center for American Archaeology was Crow Canyon’s progenitor and together, CAA and Crow Canyon did a great deal to raise awareness within the discipline of archaeology that public education about archaeological research is a part of our professional responsibility. As a result there are many programs today that provide the public with the opportunity to study our shared human past. But I don’t think there are other institutions that provide exactly the same mission and vision as Crow Canyon’s: to create a privately funded Center that can conduct long-term archaeological research to understand the human experience, a Center that has a residential facility where students of all ages can stay and participate in that research—both field excavations and laboratory analysis—and a Center that partners with American Indians to design and deliver its research and education programs,” said Mark.

In December (7 – 16) 2014, Crow Canyon Archaeological Center hosts another trip, this one to explore the ancient Maya in Belize and Guatemala. Attendees will explore the mysteries of the ancient Maya, explore sites including Caracol and Tikal and visit village and outdoor markets of the Maya world today. The exploration is led by Maya Exploration Director Dr. Ed Barnhart, who has more than 20 years experience in Mesoamerica as an archaeologist, explorer and instructor.

To register, go here or call 800 – 422-8975, ext. 141, Monday – Friday, 8 a.m. – 5 p.m (mountain time).

About Mark Varien:

Dr. Mark D. Varien, Research and Education ChairExecutive Vice President of the newly formed Crow Canyon Research Institute, has worked for Crow Canyon since 1987. Mark’s professional interests include archaeology and public education, Pueblo social organization, Pueblo migration, and American Indian involvement in archaeology. Mark earned his Ph.D. from Arizona State University. Mark’s Ph.D. dissertation on Mesa Verde region settlement patterns was awarded the Society for American Archaeology’s Best Dissertation Award, and it was later published as a book, Sedentism and Mobility in a Social Landscape: Mesa Verde and Beyond. His recent research publications include the edited volumes Seeking the Center Place: Archaeology and Ancient Communities in the Mesa Verde Region and The Social Construction of Communities: Agency, Structure and Identity in the Prehispanic Southwest. He publishes articles in many peer-reviewed journals, including Kiva, American Antiquity, Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, and World Archaeology.

About Ricky R. Lightfoot:

Dr. Ricky R. Lightfoot, former president and CEO of the Crow Canyon Archaeological Center, has conducted field work in the Four Corners region for nearly thirty years. For twenty-three years, he played a lead role in Crow Canyon’s research program. Ricky’s research has contributed new understandings of ancestral Pueblo Indian social and economic organization and thirteenth-century Pueblo competition and conflict. His book Archaeology of the House and Household is one of the foremost studies of how ancestral Pueblo farm families organized their economic activities.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.