21 Apr TIO New England: MASS MOCA & More

Zen-like quiet and profundity? Psychedelic bomb exploding? Take your pick. Both are available in three sprawling exhibitions at MASS MoCA in North Adams, Massachusetts – not to mention the wonderful work in a town house across the street.

For five decades, Richard Nonas has created a body of work whose minimalist vocabulary belies its power to fundamentally alter our sense of space, time, landscape, and architecture. His totemic sculptures—made from earthy and industrial materials that have a timeless character (wooden railroad ties, granite curbstones, massive boulders, and thick steel plates)—have reimagined space and terrain all over the world. With horizontally oriented, ground-based, and wall-mounted works executed in a wide range of dimensions and weights, Nonas has developed a vocabulary of serialized geometric forms that both command and alter their environments, while retaining an intimate, human scale.

In one of his most ambitious projects to date, the artist’s quietly powerful sculpture (or elegant floor painting) occupies and transforms MASS MoCA’s Building 5, the museum’s signature gallery, nearly a football field in length. The museum’s history as a manufacturing plant makes MASS MoCA a particularly fitting venue for Nonas, who, since his early career—when he and his peers presented guerrilla exhibitions in alternative spaces—has often been drawn to raw industrial buildings. Nonas has created a major new work specifically for the trussed, window-lined Building 5, to which he has added a selection of existing sculpture.

Richard Nonas: The Man in the Empty Space.

Here’s a review of The Man in the Empt Space from The Times Union:

Richard Nonas‘ concise steel planks and shifting timber blocks create certain expectations about what his sculptures do and what they are about. They look like straightforward examples of minimalism: comparisons to Carl Andre or Richard Serra arrive as a matter of course. But his best work is a little different, more slippery than that, more sensitive. Nonas stresses that his sculpture leads to discomfort, and this affront to expectation is part of that…

“I want every aspect of the making to be pretty straightforward, except the final result,” Nonas explained in an interview. “For the final result I want that tension, that sense of not quite making sense.”In the artist’s new exhibition at MASS MoCA, “Richard Nonas: The Man in the Empty Space” — his first museum show on the East Coast in 30 years — Nonas sets out to create the conditions for that unnamable tension, that problematic aspect that can beget new forms of seeing. Educated as an anthropologist, Nonas came to art in the late 1960s and early ’70s with a less conventional background and different set of concerns than the bulk of his peers. But he shared common ground with them. His field work in places like northern Mexico, where he once embedded himself in a village of 50 people for two years, drove him to pursue in sculpture questions of place and how it is expressed and projected…

Walk into adjacent rooms and enter a world on the other side of the looking glass (or down the rabbit hole). It is the Neo Pop world of Alex Da Corte.

The New York Times dives into Da Corte’s immersive world, in which the artist’s “riotous post-post-Pop sensibility” transforms MASS MoCA’s galleries into a “ravishing and terrifying” environment of sculpture and video installations.

Provocative, puzzling, and visually seductive, in his first museum survey Alex Da Corte’s neon-bright, exuberant works merge the languages of abstraction and modern design with banal, off-brand items, ranging from shampoo to soda to tchotchkes and household cleaning supplies.

Acid-hued and organized with a rigorous formal logic, Da Corte’s mash-ups mine products of domestic life—which he finds on pilgrimages to supermarkets, flea markets, and dollar stores—for unexpected visual appeal, as well as emotional and libidinous impact.

Heir to Pop artists of the 1960s, Da Corte combines common consumer objects with popular culture, personal family narratives—and other artists’ work—in vibrant installations of sculptures, paintings, and videos. Taking over MASS MoCA’s second-floor galleries, “Free Roses” features a selection of works made over the last 10 years, as well as a major new installation, which serves as a conceptual fulcrum for the entire show.

The centerpiece of the exhibition is a sprawling new ensemble created for the museum’s 100-foot long, 30-foot tall gallery. It is the artist’s sixth installment in a series of works based on Arthur Rimbaud’s poem “A Season in Hell.”

The young 19th-century poet’s angst-ridden prose—about self-knowledge, work, and love—is mirrored in Da Corte’s references to his suburban upbringing, teenage desire, family relationships, love, and loss.

Also on view are three videos inspired by “A Season in Hell,” along with a suite of table sculptures—a series originally developed from props used in the videos. Meticulous arrangements of items such as picture frames, plastic grapes, a Wiffle bat, and hair rollers placed atop a surface supported by sawhorses [Untitled (Buffet)], 2012, read like sophisticated time capsules. Like his predecessors Mike Kelley, Paul McCarthy, and Jim Shaw, Da Corte investigates the cultural and psychological narratives invested in the objects he manipulates.

Alex Da Corte’s “Lightning.,” courtesy, The Boston Globe.

Below is a review fly Sebastian Smee from the Boston Globe.

It is unreasonable — it is actually mad — to expect as much as we do of objects. We feel them pulsing with possibility in our jeans pockets. We squeeze them until they squirt sauce onto our plates. We slice them and toast them and suck them and cradle them, and all the time we want something from them.

In functional terms, that something is simple. In psychological terms, what we want so far surpasses anything the objects could possibly provide that to reflect on the mismatch is to become humiliatingly aware of a low drone of hysteria inside us.

You’ll know what I’m talking about as soon as you enter “Free Roses,” a demented, fluorescent, and at times quite brilliant show of sculptures, paintings, videos, and installations by Alex Da Corte at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art.

The show surveys 10 years of work by the 35-year-old, Philadelphia-based artist. Filling several large, contiguous galleries, Da Corte addresses — in a sophisticated but still-developing idiom that feels at once funny and sinister, familiar and fresh — sex, suburbia, symbolism, and stuff.

What kind of stuff? Bright-colored stuff. Food. Plastics. Plastic foods. Food dye. Liquids. Ikea furniture. Beanbags shaped like burgers. Artificial Christmas trees. Acrylic fingernails. Rhinestones. Stuffed dogs. Circling bats. Sliced bologna.

That’s right. It’s random. And yet it’s all tighter, and smarter, than it sounds…

Climb out of the acid trip (on steroids) and up a few stairs to reenter a quiet, contemplative world of tight, terse, visually engaging minimalist work. It is the world (and work) of artist Sarah Crowner. Her show is entitled “Beetle in the Leaves.”

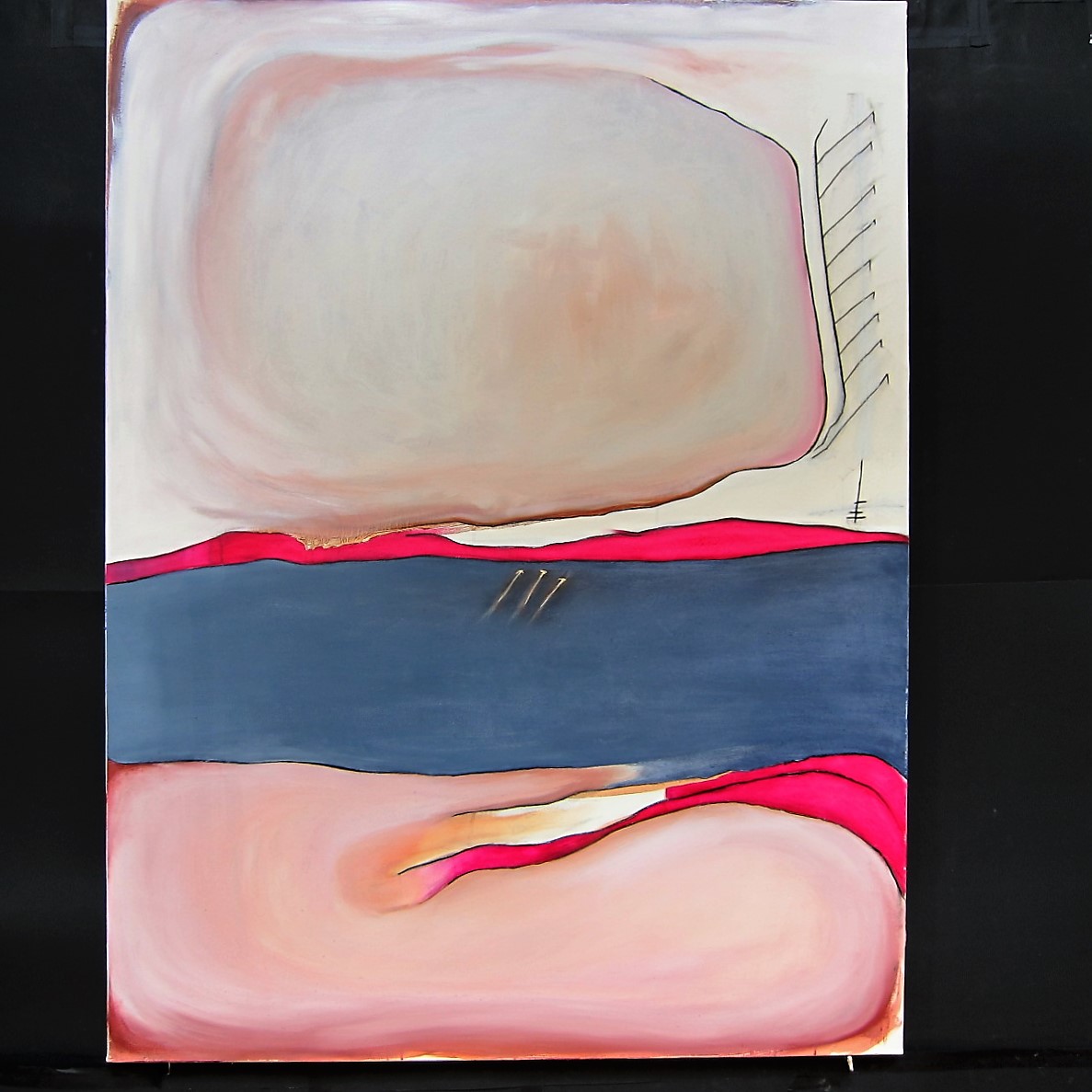

Crowner mines the legacy of abstraction from both the fine and applied arts, treating art history itself as a medium to be manipulated—sampling, collaging, and rearranging existing images to create new forms. Her practice—which includes ceramics, tile floors, sculptures, and theater curtains—centers around sewn paintings that she makes by stitching together sections of raw or painted canvas or linen. The hybrid paintings borrow from the language of collage, as well as quilting, with visible stitching functioning as both line and surface.

Crowner’s exhibition at MASS MoCA—her first solo exhibition in a U.S. museum—features both existing paintings and major tile works designed and fabricated for the show. A raised tiled floor and two tiled walls in the central gallery create a mise en abyme (i.e., a room within a room, as well as an exhibition within an exhibition). Inspired by the utopian design of modernist architect Nanda Vigo’s Casa Brindisi—conceived as both a home and a museum for Remo Brindisi’s art collection and as an experiment in the integration of the arts—Crowner’s tiled structure functions as a platform and backdrop for a selection of her large paintings. This installation invites viewers to engage directly—face to face, visually, and spatially—with the works, which in turn operate like performers on the raised stage, enveloping the viewer in the scene. The hard, glossy nature of the tiles and the hard edges of their uniform grid structure provide counterpoints to the softly textured canvas and curvilinear forms of Crowner’s paintings. Several of the artist’s large, monochrome paintings—made of sections of raw canvas sewn together and thinly outlined with frames of bright color—are presented in adjoining spaces. A new large-scale painting made from terra-cotta tiles, designed by the artist for a previous platform work and produced and hand-glazed in Mexico, literally frames the floor as a painting. Both this work and the tiled room engage directly with the geometries of the museum’s mill architecture variously mirroring and creating juxtapositions with the pattern of the brick, the direction of the boards in the hardwood floors, and the grid of glass bricks embedded in the gallery wall.

About MASS MoCA:

Aunt Con’s next show is slated for the New Marlborough Village Association starting September 2.

Connie Sussman Landscape

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.