27 Apr Outlaw Reflections: “Epoxy Deluxe”

The following is an excerpt from “EPOXY DELUXE,” a book Oleh Lysiak is working on about THE FLYING EPOXY SISTERS. The story line features both contemporary and historical Telluride and is a Telluride Inside… and Out exclusive. With muscular phrases such as “I opt to drive south along brilliant azure Pacific feathering breakers, daybreak clouds playing pink and orange grab ass over dark protruding jagged crags,” you will want to read on. Oleh’s is a testosterone-fueled, trippy trip to the region we call home.

EPOXY DELUXE

Three naked Flying Epoxy Sisters, snug butt to belly in three sets of bindings mounted on one pair of downhills, ski past Goronno, Telluride’s mid-mountain restaurant, in full, glorious view of skiers enjoying sunshine and lunch.

The Sisters wear dresses to the Roma, Last Dollar and Sheridan in a latch-ditch effort to get laid. Telluride women, disarmed by seven brazen, essential, sensitive Vermont men in free box girlie fashions and ski boots, open minds, hearts and legs.

When there’s no snow in Telluride the Sisters hold a ski sacrifice and burn a giant stack of skis on Main Street. It snows the next day. They run ski shops, dedicated boilerplate pros from the East. The Sisters ski The Spiral Stairs and The Plunge, balls to the wall Double Diamonds, and powder out of bounds stoned on acid; warp and weft of Telluride’s legendary fabric.

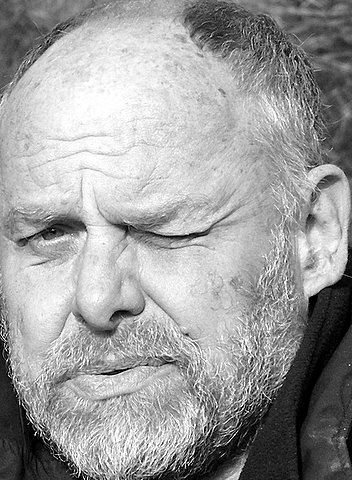

Peter Chapman, Clarke Comollo, Peter Langstaff, Eric Liekefet, Flying Epoxy Sisters at Rob Funkhouser’s memorial in Norwood in 2007, the last time they were together.

Of seven original Flying Epoxy Sisters, five survive. Peter Chapman is in Colorado; Eric Liekefet in Florida; Clarke Comollo, Peter Langstaff and Jim Huelett in Vermont. Geoffrey Chapman, Peter’s brother, died of cancer in 1983. Rob Funkhouser died of a heart attack in 2007. Eric survived open-heart surgery last year. Huelett is reclusive.

Surfing the web one 4 a.m. I encounter a site devoted to The Flying Epoxy Sisters, guys I know from Telluride in the late 70s, early 80s. They leave an indelible mark on the town, infamous. I get in touch with Clarke Comollo, the Sister who posted the site, and propose we do a book. He contacts surviving Sisters. Everybody’s in.

Clarke posts this anonymous paragraph on his Flying Epoxy Sisters website:

“… in this little town of Telluride there was a higher level of skier. There were the Epoxy Sisters, a group of guys who lived to ski, and their natural skills went far beyond the abilities of any competition skier I knew. These guys would ski out of bounds; the chutes, the cliffs, and the trees, anywhere they could find virgin snow. You may see them on an early chairlift, and then they would disappear as they hiked into the backcountry in search of fresh snow, and maybe you would see them at twilight heading home. These guys didn’t have the newest high-tech equipment, but they took great care of their skis. Their clothes were torn from the trees and rocks and patched with various bright ideas. They devised new ways to solve problems such as using snorkels for skiing the fluffy, dry powder snow so the ice crystals wouldn’t fill their lungs and burn. They didn’t ski for ribbons and medals; they didn’t ski for Warren Miller. They skied for the simple glory of the moment, that clear consciousness of doing what they loved to do. I remember sitting on the ski bus across from a guy – old ski suit, duct tape here, duct tape there, snot and icicles frozen to his beard, a snorkel dangling from his head – and I knew I was in the presence of greatness.”

It’s been more than 20 years since I last saw these guys. Friends back in day, we occasionally shared drugs as accepted social custom in early New Telluride, swapped parts working our respective ski shops, but I never attended their pig roasts or ski sacrifices. Ten years older, I was married by the time they arrived in town, doing my own thing my own way, not a joiner. Acid was history for me by then. We didn’t ski together. They were much better skiers. In a town where actual avalanches compete with gossip for sheer volume and destructive capacity, I heard Flying Epoxy Sisters exploits on the grapevine almost daily.

Flying is a last resort for me. I prefer to drive, sleep in my own bed, cook my own meals, schedule dependent on whim and weather. The TSA can amuse itself with contemporary citizen victims addicted to overcrowded airports, unreliable schedules, cancelled flights, overpriced fares, paid luggage, exorbitantly priced mediocre food, lousy service, an even lousier attitude, all in the name of business, facility and convenience. They get what they pay for and deserve it.

My road rig for the past 10 years is a way-too-cool aerodynamic aluminum 1967 Avion truck camper on a 1995 Dodge Cummins 3/4-ton 4X4 5-speed pickup, retro elegance with diesel moxie. The Avion’s cool quotient sports leaks and rot after 47 years, a shaky proposition for a pedal-to-the-metal transcontinental rip. It sells to a Southern California woman desperate for cool, willing to restore the needy beast. She wires money and arranges freight. I buy a local 1992 Caribou camper built in Oregon: spacious, solid, functional and modestly contemporary with implied geezer anonymity.

Spring snows wallop passes over the Cascades, Siskiyous and Sierras, no letup in immediate forecast. I opt to drive south along brilliant azure Pacific feathering breakers, daybreak clouds playing pink and orange grab ass over dark protruding jagged crags capped with gull and puffin excretions. I love this road! No white-knuckle, hang on for dear life testosterone extravaganza for me. I’m old and savvy enough to take it easy. The longest way around often is the shortest way home, something I learned sixty plus years ago from Dick, Jane and Spot in an elementary school reader.

Hours later I’m on a dirt road deep in redwoods high in Northern California’s Coast Range. Dewy silence surrounds the house, hangs over shaggy-barked forest, a scenario of diffused light in massive vertical presence, spiced with pungency of rotting leaves and spongy fungi. Nobody home. Dogs bark. I open the front door. Tumba, my favorite dog palooka, greets me in bounds with slobber and drops a venerable wet gray tennis ball at my feet. More dogs bark locked in on the porch. I leave them incarcerated, having endured their main dog Nazi’s wrath for overstepping human-canine boundaries before. I pick up the ball. Tumba leaps for the door.

I launch and Tumba retrieves around the property. New fences enclose fresh dirt tilled for gardens replacing previously voluminous lawn. A wood-fired bread oven sports charred deer antlers, awaits coals and dough. The platform in the apple tree I built when the boys reached my waist is black and gray but still there. Tumba decides to eat the ball. Doggie withdrawl momentarily stoked, I go inside.

Mobiles given to the family over decades hang in varying stages of disarray. One after another I tune them. My favorite sis, the boys’ mother, walks in the door. Hugs, kisses and smiles. Her husband, the dog nazi, is fishing albacore. They boys will be home soon from work.

Regulation and political correctness put severe restrictions on logging, agriculture and fishing, local industries of choice over generations. Most families in the area now have medical marijuana certificates. They boys’ grandfather was a logger, worked in vertical cellulose. The boys make do with local opportunity and work in THC-producing cellulose closer to the ground. It’s all hard work, but times are changing. Local law knows how its toast is buttered. Feds are viewed with suspicion and derision.

The boys, both taller than me, are now strong, capable men. They walk in dirty, tired, smiling. More hugs. Dogs from the porch join the party. Stories around the dinner table accelerate. Good smells emanate from the kitchen. Sis rules.

On the road before daybreak, I’m on Interstate 5 tuning in to Sacramento’s NPR FM stations for news, even if they’re slanted somewhat to the left. AM talk stations shamelessly expound Christian extreme right doctrine washed in the blood of Jesus or redneck Obama bashing, inane beyond boring. Mexican stations proliferate boohoo corazon, salsa or mariachi music, without political bullshit of either extreme: no credito, no dinero, no problema!

Interstate entertainment this morning is a miles-long, all-woman caravan of 50s and 60s trailers: Spartan, Avion, Styleline, Aristocrat, Boles-Aero Zenith, Airstream Safari, Shasta Airflyte and Canned Ham all tricked out, cute, polished and painted retro like they vacation with Lucy and Ricky.

They turn for Interstate 80 to Tahoe. I steer south for Lodi, Stockton, Manteca, and Los Banos, volume up on a hot FM classical station with no commercial interruption. The Cummins diesel does a steady 70mph on cruise control. We run with semi caravans, occasionally passing slower rigs. Fast-lane aficionados in high-performance late model luxo-rigs hammer accelerators, anxious to breathe LA smog or crash tailgating; dangerous idiots. When a safe opportunity for the slow lane presents itself, I signal lane change, take my time making the transition, wave and smile. Of course they think I’m an asshole for having the temerity to impede egomaniacal progress. Adios, motherfuckers.

The Sierra Nevadas in the distance to the east cloud over with occasional breaks exposing snowy peaks. Pressing south through San Joaquin Valley orchards, feedlots, and endless produce rows past Coalinga, Avenal, Wasco, Shaftner, Buttonwillow, Pumpkin Center, I exit for Weedpatch and Arvin on a rural two lane in wheat fields and vineyards teeming green, with farm houses and mansions from a more elegant era punctuated by stately towering palms defining elongated driveways.

The two-lane road out of Arvin rises extreme up valley with occasional turnouts to pass trucks flashing on a low gear grind to the summit, view spectacular: geometric fields in multifarious greens lit acre across acre by intimations of rose-orange sunset over the Coast Range filtered through voluminous cleavage of cumulus billows highlighted by sporadic angled light streaks. I consider a photograph but instead sit in awe until light fades. The lens on my Nikon won’t capture this enormity.

On the valley floor Interstate 5 and California Highway 99 merge into a high-speed 8-lane concrete monstrosity south and west over the Grapevine into LA megalopolis. On a mission with no inclination or time to dally in polluted and violent urban sprawl, I crest the summit east and finally, no snow.

A law-abiding geezer sans dummy dust, whites, alcohol, acid, shrooms, pot or mescaline to enhance my journey, I’m content to enjoy the view from my reasonable diesel camper at the legal limit, nothing to fear from federal, state or local cops. You can’t go to jail for what you’re thinking unless you blab.

On a mission, drugs superfluous, I’m focused, and make the turn for Highway 58 to Tehachapi, Barstow and Interstate 15 for Las Vegas. A memorable FM station out of Lancaster-Palmdale simmers spicy rock and roll.

The station fades as the entrance to Interstate 15 appears in the dark on the outskirts of Barstow. Exhausted, my plan to pull over for the night at the first rest stop towards Las Vegas is thwarted by a highly visible CLOSED sign. Guided by strobe lights and reflectors in the slow lane, semis flashing in the truck lane, I scan the fast lane in the mirrors for approaching headlights and gauge closing speed. An hour and a half up the relentless gradient is an open rest stop. Beyond tired, I park to the side of brightly lighted facilities close to the exit in a large gravel lot, spent, in the zone, buzzing, climb into the camper and crash.

At 5,000’ between the New York Mountains and Silurian Hills close to the Nevada border, cold wakes me at 2:30 a.m. In seconds cheery bright blue circular propane flames heat water and warm the rig. Ground coffee eyeballed into the Melitta filter is topped with steaming hot water in the chipped enameled camp pot and nasty black’s familiar aroma rolls in the camper, homey. Last night’s empty lot is rife with parked semis, running lights blazing, diesels humming.

Thermos full in road flow at a quarter to three in the slow lane, I check oil pressure, engine temperature and alternator gauges, Cummins rhythm, defroster toasty on windshield, and pour a six count into the cup in the retractable dash holder. Awake, locked in, rolling, Las Vegas glare lights cloud bellies in the distance. Fuel gauge indicates a diesel stop soon as I pass neon-lit construction zones defined by a phalanx of orange traffic barrels garish with pink luminescent tape and a lone yellow taxi streaking for the final casino row exit. First Flying J past the lure of bright lights and billboards I add top end lubricant, fuel up, wash windshield; check oil, radiator reservoir coolant, wheels, tires, tie downs, headlights, taillights and running lights, good to go home on the road again.

A normally entertaining ride through the Virgin River Canyon, among the best road shows erosion offers at 70 mph, is ruined this morning by serious construction and constricted lanes. I concentrate on avoiding anxious oncoming behemoth motor homes and bring up the rear of a semi convoy hemmed in from behind by a miles-long road snake.

Fuel is unavailable from Salina to Green River, a 110-mile stretch of spectacular high desert desolation. I stop for early diesel and breakfast. It’s snowing lightly, in an intermittent cloud and light extravaganza since the Utah border. Slush startles sockless feet in Crocs as I step out of the Dodge. Back into the camper, I dry feet and Crocs and pull on socks. The truck stop features a Jack In The Box. I order two fish sandwiches for breakfast and make a fresh pot of nasty black.

Cruise control on 70mph, Nikon on the dash wide-angle lens open full bore or aimed approximately out either window, visions and revisions flash by in Maynard Dixon-like landscapes, mesas and mountains miniscule, clouds and sky beyond immense breathing San Rafael Swell. Hammer down, wired to the bone, I need to stop before I piss my pants. Luckily this stretch of desolation offers handy turnouts. Grudgingly, I pull over, relief. Some things a guy just can’t ignore.

Early afternoon I turn off Interstate 70 for Moab, snowcapped La Sals prominent, tourists, sight seers, 4-wheelers, bicyclists, rafters, kayakers, hikers, campers; two cops parked in either direction on the downhill median above the entrance to Arches National Park. I cross the Colorado River, bumper to bumper along stripmall mega-motel row. Billboards abound. Moab’s changed.

First left at the Post Office, a right on Fourth Street, I’m at Serena’s house across the street from Dave’s Corner Market. Back street Moab remains reasonable although the parking lot at Milt’s burger joint neighboring on Dave’s overflows.

Serena explains the Main Street circus is the cost of doing business and the price of progress, a pittance considering economic viability in remote, scenic and spectacular desert, central to Arches, Canyonlands, Cataract Canyon, The Colorado River, and the La Sal Mountains. I think about what she says. We’re been friends for 30 years and don’t bullshit each other. If solitude is what you’re after, go deeper into remote wildness or in a season when tourists are gone.

Serena earns her living exclusively with art. I bought my first Serena painting in 1985. She now produces large oils, watercolors, prints, calendars, cards; designs stained glass windows, weavings and the annual Phantom Ranch T-shirt. A well-known and respected Southwest artist, Serena is dedicated, obsessed, specific, her time precious and devoted to sketching, painting and promoting. Peeved I arrive a day early, not on her committed timeline, she’s due to paint an oil on site on the Double Arch Trail from 4 -7 this afternoon, the Arches National Park Community Artist for 2014 April through September.

Serena suggests I meet her at the painting site, but knows I’m adamantly opposed to a $20 entrance fee to walk on federal land, which essentially belongs to we the people. We go together. Van packed, Serena drives through the Arches checkpoint, waves at the uniformed federal female ranger replete with gold badge and Smokey the Bear hat and we’re off for Double Arch, on a road through phantasmagoric erosion, a tour of old friends.

The sky is flat gray today, no contrast. The wind blows cold. Serena sets up and paints orange, purple and hot pink in the parking lot. Tourists, gawkers and passers-by slow down for a glance. Few stop to talk. One memorable brunette in an off-shoulder blouse speaks throaty French Polynesian-spiced English. She’d love to stay longer and chat, but her husband, who claims she talks too much, waits impatiently in the rental.

On the stroke of seven we pack up and stop for Thai food on the way home. Serena announces she’s taking tomorrow off. We’re going to Island in the Sky in Canyonlands in her new Toyota FJ 4×4.

I bring albacore salad sandwiches and oranges for lunch. We pack gallons of water and fuel up early at the City Market. Another uniformed federal female employee checks Serena’s pass at the Island in the Sky entrance. Voluminous cumulus billows, from foreboding to heavenly pearl, cool morning. Serena pulls over on cue. I compose, Nikon in hand, views continually startling. On the steep switchbacks to the White Rim Trail above the Colorado River we leave tourists behind save occasional neon-bright Kevlar-armored trail bike riders looking to get by old slowpokes.

And yet another uniformed federal female ranger with a gold badge, packing a 9mm and a Smokey the Bear hat, waves us on at the White Rim Trail junction. We’re in a yellow late model Toyota FJ and obviously have our shit together. I wave back and smile. Serena calls it the Right Whim Trail. About 40 years ago I drove this same trail in a 1948 GMC pickup with a pal and his girlfriend when there were no fees or rangers or regulations about what you could or should do. Responsible and capable, we did what we pleased, packed our shit out and went home. We didn’t need politically correct wannabe government cops packing badges and heat to charge us for using what was ours already or regulate our wilderness experience. Times and attitudes apparently have changed to where we need protection from ourselves, from our wanton dedication to the lowest common denominator, sad.

We stop for lunch at Musselman Arch, where I did a yoga headstand naked, on the 48 GMC pickup ride, wouldn’t dream of trying it today.

Serena sketches what catches her eye. I shoot frame after digital frame. Early afternoon we go home, today a visual onslaught, incomparable, more than I can immediately process.

Back in Moab there’s an email from Peter Chapman. He walked into the bar at the Sheridan Hotel in Telluride a week ago and announced he’s through with women and drinking. As Fate would have it, a tall, slim looker with a spectacular toned butt is at the bar when he makes his announcement. She suggests they drink tequila. Freshly fucked, Peter glows through his email.

He knows days ago but waits to tell me until he’s certain I’ll show up. Incurable and or hopeless romantic are woefully inadequate describing Peter. He’s a junkie in love with being in love, hooked on intense speculation after a hot piece of ass. This may be THE ONE, maybe.

We’ll meet in a couple of days at his place outside Norwood. Before departure I tune Serena’s mobiles. After hugs next morning I make a left at the LaSal turnoff south of Moab.

The spring at the hairpins above the Colorado border no longer flows free, now tamed and tapped with a faucet. I stopped here for decades. In winter the spring was an ice and light show frozen in fractal patterns along an ancient rusted hog wire fence. This morning I pass, hot for a glimpse of Paradox Valley’s stark, wild, stunning red rock, unfettered, uncivilized, familiar, unchanged.

The Bedrock Store, where Butch, Sundance and the Hole in the Wall Gang stopped for supplies, is shut. I stop and holler hoping singer, songwriter and most recent owner Rose Morse will open. No response. I drive on, no noticeable change on the highway through Naturita and Redvale. Big Green, my old Dodge dump truck sits faded, parked in the yard at Zehm’s Tree Farm. The Saab 99 with the UKRAINE sticker I drove to Telluride eras ago no longer occupies a spot high in the fence protecting Darryl Elder’s American automotive art junkyard and hog farm. Darryl died. His son mashed out the fence.

Norwood’s changes seem superficial as I drive past 1360 Cedar Street, my former home. Neighborhood’s the same as the attitude on Wright’s Mesa where I once waged war with the town’s mayor and the east end of the county reporting for The San Miguel County Post, something few remember today.

Top of Norwood Hill I head south on fate magnets along the last county road for Rob Funkhouser’s place. Last time I saw Funky was for dinner in 1995 in the Victorian house he was so proud of. The house burned down. Rob died of a heart attack in Vermont in 2007. He was 50. Peter Chapman bought Rob’s property and is rebuilding the homesteader cabin Rob intended to.

Peter’s in love, no telling when he’ll show up. I pull in, park level and cook breakfast, local anywhere but especially here.

Peter suggested we meet in Telluride where he has use of a condo and tickets for the ski area closing street dance. I politely declined because I’m here to work, on a mission with no time for Telluride nonsense, which I passed on 20 years ago having indulged in way more than my share. I suggested we meet in Norwood instead.

The San Juans and Telluride sparkle in spring snow to the east, Tukhanikavits and LaSals to the west, Lone Cone to the south and the San Miguel River to the north. I meander around Peter’s 17 acres, and photograph views, rusted relics, rickety fire-singed outhouse, vintage chicken coop and fire survivor cabin.

Late morning Peter and his true pregnant love Bella arrive in a Subaru station wagon. Bella immediately checks me out sniffing, determines I’m OK and wags greetings. Peter and I eyeball each other and hug smiling, old home week on Wright’s Mesa, pats on the back. Peter spackles and paints the inside of the cabin, hot to get it done before winter with a fresh love to service in Telluride and painting jobs waiting on the East Coast. I lock into WIFI and set up my tape recorder. Bella picks a shady spot on the porch with a groan.

My tape recorder is a 20-year-old Olympus I used while a reporter for The San Miguel County Post. Fresh batteries and a sound check, I’m ready. Peter mixes paint, sets up a ladder and a makeshift scaffold. We go to work.

Peter and I share each other’s bachelor cooking for days. Interviews done, we drive to Norwood for a celebratory dinner.

The Lone Cone Saloon, our best choice for dinner is shut, unusual, a For Sale sign on the entrance. I was looking forward to seeing Chef, the good-natured Swiss transplant owner, bartender and cook at the Lone Cone for as long as I remember. We make a tour of Main Street. Nothing open. A brief stop at Clark’s Market for deli take out in the trailer, I spot a pizza joint tucked away nonchalantly on the left side middle of the last block leaving town. Peter throws a U-ie.

The place is done up as a Tuscan sports bar on the road between Telluride and Moab. A frizzy-haired woman with a sense of humor and an infectious smile takes our order. I order a large veggie pizza and a root beer, micro-brew for Peter. A hockey game plays on the large screen TV, nothing better! The pizza is delicious, company lively and the never-ending game gets more never-ending.

This morning a big red-tailed hawk soars overhead, lets loose a series of high-pitched cries. Peter looks up, smiles and whistles at the hawk, believes Funky’s spirit is in the hawk keeping an eye on the land. I believe it too, no reason not to.

Oatmeal in a cup for breakfast in hand, Peter settles in a chair facing the sun. Bella hears his whistle and settles by the chair.

“Sing, Bella, sing,” Peter cajoles.

Pregnant Bella rises and lets out soulful, mournful, modulated howls, increasingly excited. Peter howls along with Bella. I howl along in enthusiastic dissonance until we can howl no more.

After breakfast Peter empties the car top carrier on his Subaru of multiple pairs of skis. Donny Hannah called last night inviting Peter to go late spring skiing in Snowbird. Donny has lift tickets and lodging arranged. Peter arranges for a Norwood pal to take care of Bella while he’s skiing in Utah. Packed for the trip, he’s ready to go. Bella loads up in the Subaru. Peter and I hug. He waves, makes a left and is gone.

Hawks circle in cerulean Colorado-clear sky. I’m motionless in waves of what just transpired. Nearly 20 years ago Rob Funkhouser invited me to dinner in the Victorian he shared with his girlfriend Dietra on this land. I had just quit my job at The San Miguel County Post and was writing a novel, broke, living on potato pancakes and coffee. Rob gave me a job roofing. I lasted two days. He paid me for the two days and invited me to dinner.

The Victorian Rob was so proud of burned to the ground, his ashes scattered out of Clarke’s cannon over where the Victorian stood. Peter is rebuilding the cabin Rob intended to for his home.

I stand silent, subcutaneous emotional bumper cars running amuck between the LaSals and Uncompaghres. Red-tailed hawks soar. Faded Tibetan prayer flags flutter from the porch on the cabin. I’m grateful for this opportunity to know Peter Chapman 30 years later, like discovering a brother. Time mitigates bravado. If you’re lucky you survive.

Mountains shimmer pregnant with spring snow. A glance off Norwood Hill’s familiar curves reveals thaw runoff streaking opaque in the San Miguel, currents roil in chill riffs, snow and ice recede between bare cottonwoods along the banks. No fishermen today, too early.

As a matter of courtesy I warn friends when I intend to be in their neighborhood in case they should develop a sudden need to be out of town, consideration developed after edgy decades. I called Socko from Oregon to warn him. We haven’t seen each other in 20 years, nor have we spoken.

“Yo, Sock,” I begin after a two decade hiatus.

“Hey, O,” Socko says never missing a beat, “how are you?”

I don’t have a lot of time for visiting, but Adrian and Socko are on my “A” list. When I left Telluride and San Miguel County, I didn’t look back. I’m not having second thoughts, but there are people here I cherish.

A left on the dirt road to the park and fire station, past the house I built and donated to my ex-wife in the divorce, nary a twinge, bleached bones of one dream, hot meat of another. Unfamiliar cars are parked along the fence I built. The silvered streaked fence looks good.

Socko is the Ski Patrol Supervisor and has worked on the Telluride ski area longer than any other employee, 40-plus years. He swears he’ll retire next year.

Adrian and Socko make it work in Telluride on their own terms, stylish, in shape with great attitude, enthusiasm, skiing the lifestyle with annual off-season camping vacations in Baja or ski patrol exchanges in France. They live in a home they designed and built down valley.

After dinner, followed by tales tall and short, I ask Socko what he thinks of the Flying Epoxy Sisters. He chased them out of bounds into avalanche dangerous terrain on occasion.

Soko takes time to answer.

“They were SKIERS,” he says.

It’s not the simplicity of his assessment, but the tone with which he delivers it, with implied respect of a skiing professional for acid-crazed edge mongers who skied with abandon for love; performance art enthusiastically insane and glorious in the moment. They were lucky and survived.

Oatmeal breakfast, pix for the archives, Adrian and Socko are hot to pack for their annual Baja camping trip, goodbyes and hugs.

Top of Keystone the mountains surrounding Telluride astound as usual. Roundabout at Society Turn I flip Telluride the bird, make a right on 145, and adios, motherfuckers, I’m on a mission. As far as I’m concerned, the only thing about Telluride that has improved is the skiing. I was done with the town in the mid 80s, a nice enough place with some good people, but just another cute stop along the road surrounded by spectacular mountains.

Achromatic 14,246’ Mount Wilson is spectacular against cloudless Uncompaghre pale azurite sky, Ophir Wall not chopped liver, snow piled high up both sides of the road on 10,222’ Lizard Head Pass. Windows down, I shoot frame after digital frame of reasons I spent 20 years here.

Editor’s note about Oleh:

I am reminded of the man every day. A talented sculptor, one of his mobiles sits on the coffee table in our living room. But I had not seen or heard from Oleh Lysiak for over 20 years. Ah, the wonders of social media. We rediscovered each other about a year ago, which was when I also discovered the artist is also a writer – at least nowadays – though making marks on paper is only one among a very long list of talents, some slightly sketchy.

A former Telluride resident, O.Z. Lysiak once worked as a San Miguel County journalist. He is also, as mentioned, an artist, author and poet. Two of his books: “Art, Crime & Lithium” and “Neighborhood of Strangers” are now available at The Wilkinson Public Library.

Given his street cred and the fact he wrote extensively locally in the bad old days, I asked Oleh if he would mine his files for past columns that might be of interest to our readers. I am thankful the man said “yes.”

The column name? We hold certain truths to be self-evident.

Donna Joywalker

Posted at 05:34h, 05 MayLOVED reading this! Lived in P-ville and T-ride late 70’s to early 80’s and frequented all these lovely haunts! Some of the best times of my life. Thanks!