07 Oct TIO NYC: Zao Wou-Ki, “No Limits”

East meets West at a show up now at Asia Society, 725 Park Avenue (through January 8): Zao Wou-Ki “No Limits” takes the viewer through the life and work of work of a master of post-WWII abstraction.

According to the show’s curator, Boon Hui Tan, Vice-president for Global Arts & Cultural Programs and Museum Director, Asia Society:

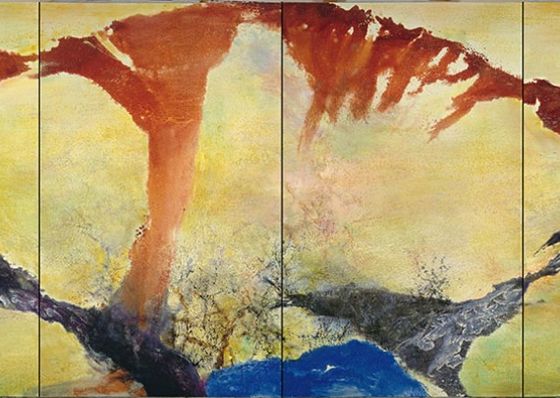

Zao Wou-Ki (1920–2013) created a unique pictorial language shaped by diverse influences. Throughout his long career, Zao’s experimentations in oil on canvas, ink on paper, lithography, engraving, and watercolor, allowed each image to evolve from the next, without imposing boundaries. As an artist, he came to inhabit his given name, Wou-Ki, or 無極 “no limits.”

Zao Wou-Ki began his formal artistic training at the age of fifteen at the newly established National Academy of Fine Arts (now China Academy of Art) located in Hangzhou. In 1948 Zao immigrated to Paris and soon took the international art world by storm. Over the course of the next six decades, Zao became a major presence in Europe, America, and Asia, and now stands out as an exemplar of the global scope of modern abstraction.

No Limits: Zao Wou-Ki is the first museum retrospective of the artist’s work in the United States. Drawing together key works from public and private collections in America, Europe, and Asia, this exhibition of Zao’s works illustrates the encounter between Asian aesthetics and international art movements that came to define postwar abstract painting. His artistic practice and innovative methods reveal the dynamic cross-cultural circulation of ideas and images, and the role Zao played in the creation of a modernist aesthetic that was a truly pluralistic phenomenon.

Here’s what Roberta Smith of the New York Times had to say about the show, which takes viewers through the evoluation of the work of a man who appears to have seamlessly, colorfully, bridged the cultural gap between his two worlds, garnering accolades from both.

The painter Zao Wou-Ki (1920-2013) is by now one of the best-known Chinese painters of the 20th century. It helped that he lived in Paris from 1948 on and that his gestural abstractions, which drew on Eastern and Western sources, enjoyed great success in Europe and the United States. By 1952 he had had solo shows in Paris and New York and went on to be collected by many museums on both continents. In New York he exhibited in the late 1950s and ’60s at Samuel Kootz’s gallery, an Abstract Expressionist stalwart.

“Zao Wou-Ki: No Limits” at Asia Society is the first comprehensive show of the artist’s work in the United States. It is an intriguing, peripatetic, at times beautiful affair of 60 works from 1943 to 2003, with paintings on canvas and paper, watercolors and several kinds of prints. Yet Zao slips through your fingers, running hot then cold, refusing to settle down. He had an amazing facility. Even when you don’t especially like a painting, you may find yourself stuck in front of it wondering, How did he do that?

This show and its catalog are a good start, a base for future curators and scholars to build on. But the goal here seems to be to outline Zao’s trajectory and the multiplicity of his styles and mediums, rather than to concentrate on his best work. This conclusion is encouraged by several enticing pieces reproduced in the catalog that are not in the show, and also by a few memorable paintings that stand head and shoulders above the rest.

Michelle Yun, the Asia Society curator who organized the show — expanding on a smaller effort at the Colby College Museum of Art — would like us to see Zao as “a master of postwar abstraction equal to the giants of the Abstract Expressionist movement.” In her catalog essay Ankeney Weitz, who co-organized the Colby show with Melissa Walt, notes that Zao’s art matured in Paris and describes him as “undoubtedly a French painter of the postwar School of Paris,” though he “never entirely let go of his Chinese training.”

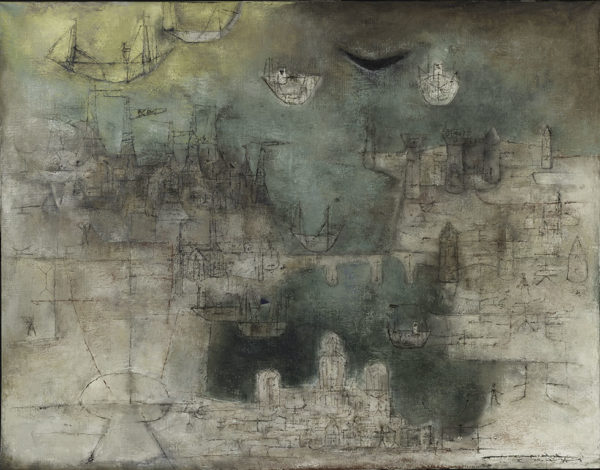

Zao comes across here as an artist who brought an Asian element to Abstract Expressionism — a style already indebted to Asian art — in a reverse cross-fertilization similar to that of the Japanese Gutai group. The show confirms that throughout his life, and in whatever style, he seems to have always been more comfortable on paper than canvas, especially as his canvases grew larger. An exhibition of prints at the Cincinnati Art Museum in 1954 — his first in an American museum — is especially impressive considering that he only took up printmaking in Paris. His virtually instant affinity is evident in three 1950 lithographs made for a book of poetry by his greatest French friend, the artist and writer Henri Michaux, and nearly every other print on view.

There is a case to make that Zao did his most confident, authentic work — and cultural fusions — while still in China or during his first years in Paris, before Chinese calligraphy and landscape painting began to guide him toward abstraction around 1955. At the time he remained under the spell of Cézanne and especially Paul Klee (who was also greatly influenced by non-Western art). As Zao’s paintings start to carom stylistically toward the end of the show, you may wonder if his career is not a striking instance of talent subverted by ambition. A desire to play in the center ring may have led him to leave his true gifts undeveloped.

Zao’s desire to fuse different elements of Asian and Western cultures into a single contemporary style formed early and probably inevitably. He was born into comfort and privilege in 1920 in Beijing. and spent his early years in the city of Nantong, …

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.