20 Apr TIO NYC: Whitney + Guggenheim + Chelsea Lite

The 78th installment of the Whitney Biennial, the longest running survey of contemporary American art, features 63 artists at various ages and stages of life and work. The art happening is now through June 11 at the Whitney, the first in the relatively new Renzo Piano building, a masterpiece unto itself.

Whitney Biennial 2017:

Dana Shutz, Elevator, courtesy, Whitney Museum.

Dana Schutz was one of two artists Michael Goldberg, co-owner (with his wife Ashley Hayward) of the Telluride Gallery of Fine Art advised us not to miss at the Biennial.

Schutz, an emerging master, is a painter of the human condition, which she represents in big, bold brush strokes and colors, but sets in the mundane context of the everyday world.

Schutz’s work, at once poignant and monumental, tends to be organized around enclosed spaces, people contained and crowded together. In her “Elevator,” (2017), individuals are piled up against one another, cheek by jowl with ginormous insects, making an obvious, metaphorical point..

Schutz is also no stranger to controversy.

In fact, in one very particular instance, she seemed to invite it.

Schutz’s “Casket” depicts the dead and mutilated body of Emmet Til, the African-American teenager tortured and lynched in Mississippi in 1956 at the age of 14 after being falsely accused of flirting with a white woman. The (mostly black) protesters argued that a white woman has no business “…to transmute Black suffering into profit and fun,” (as artist Hannah Black stated).

Some did not want to see “Casket” hung in the Biennial at all, to which Shultz wrote in reply: “Museums must be engaged in enduring history.”

And in an addendum to her narrative about the painting – crafted to send a clear message to the naysayers – the artist explains that “Casket” will never be for sale.

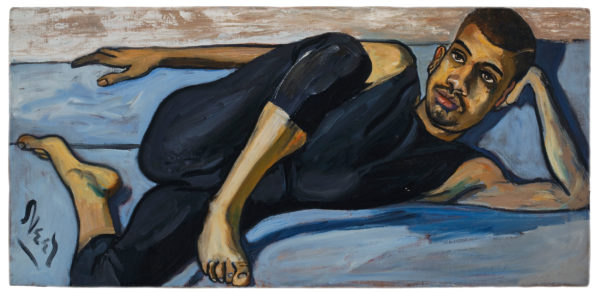

The other artist on Goldberg’s short list was Henry Taylor, known for quick, loose, relatively stark portraits of relatives, friends, celebrities, and athletes. The fact the man was once a psychiatric nurse helps explain the warmth and humanity that imbues the work, which tips its hat to the narrative paintings of iconic artists Jacob Lawrence and Romare Bearden, which also portray the good, bad, and ugly of the black experience.

Henry Taylor’s Ghengis Khan with Black Man on Horse, the painting dominates a full wall as you step off the elevator onto the 6th floor of the museum.

“I paint those subjects I have love and sympathy for,” Taylor once said.

Curated during the contentious election campaign, controversy – political, socio-cultural, environmental – is at the heart of the Whitney survey of the American art scene. And just like the 77 installations that preceded this year’s event, the show is as diverse, complex, and compelling as our country, the art world mirroring the social tensions, economic inequalities, and polarizing politics of America today.

However, some of the work is simply, unapologetically beautiful.

Carrie Moyer is an avowed feminist, known to mix and match abstracts shapes with waterfalls of pure color, glitter, and veils of acrylic – like Helen Frankenthaler and other Color Field painters of note – with some forms referencing feminist iconography, such as the Venus of Willendorf.

Telluride local Ronna Stamm seated in front on the Moyer’s painting she and husband Paul Lehman donated to the Whitney.

Some of the art on display, primarily on the museums 5th and 6th floors, is pure bonkers.

Pope.L’s “Claim,” at least on the surface, is about, I recall, the number of Jewish people now living in Manhattan. The installation is a giant box, which anyone can enter, covered with 2,755 slices of rotting, curled up bologna. The artist is making a point about data collection, i.e., the practice stinks to high heaven.

Another examples of funny/not funny is the work of Jon Kessler, whose obsession is how climate change is affecting our planet, from mass migrations (“Exodus’) to the loss of animal habitats, and rising sea levels. Kessler’s “The Floating World” is a sculpture (2016) which features mannequins in snorkel gear taking selfies as water rises and falls around their bodies.

Raul de Nieves’s parade of elaborately beaded figures and floor-to-ceiling stained glass-like panels is an elaborate installation about death – but not vintage Grim Reaper, rather as an opportunity for rebirth and personal transformation. (An idea supported by dream theory.)

The 2017 Biennial was distinguished by the number of beautiful paintings the curators selected for the show.

In addition to Schutz’s work, high on that list are the lyrical, minimalist canvases of former Abstract Expressionist Jo Baer. Artifacts, buildings, landscapes emerging from washes of gray fields stand in for cultures way past, just past, and now, dreamscapes the artist has described as “metaphoric worlds.” Not revolutionary, but wonderful additions to the overall mix.

“Debtfair” (2012-17) is a huge installation by the largely New York-based group, Occupy Museums. The piece emerged from the Occupy Wall Street campaign. Text and images are used to address the plight of contemporary artists, many burdened with financial debt, mainly from student loans. Loans are shown relative to the profiteers of our booming “art-as-asset” economy.

Footnote: That work, like all the work in the show, was selected just before he became president. Now, with cuts in federal funding for the arts, the situation is worse. The gap just became a gaping maw.

One of the best examples of environmental activism is Asad Raza’s “Root sequence. Mother tongue,” an installation of 26 trees – cherry, birch, persimmon, and others at different stages of growth, budding, leafing, blooming – set in a gallery near a sunrise-facing wall. Some of the planters feature “signatures” of their caretakers, a book here; a glove there. Is the artist saying the worker bees are the “real artists” in this story?

Like the Raza piece, another installation offering an opportunity to exhale at this ofttimes overwhelming show, is a majestic suite of red laminated glass boxes by West Coast minimalist Larry Bell, like Baer, among the show’s better known veterans. Bell’s lifelong preoccupation has been the impact of light on surfaces and of his sculptural art on its environment.

Go here for more on artists you know – and should get to know.

Chelsea in brief: Alice Neel at Zwirner; Enrique Martinez Celaya at Shainman & Tia Pol:

Follow the breadcrumbs – and the crowds – marching in lock step along the magical High Line and you come to Chelsea, a major art district, where our primary objective was the David Zwirner Gallery, 525 West 19th Street, and “Alice Neel, Uptown,” (only through April 22).

The wonderful show of empathic, expressionistic portraits of the artist’s neighbors, icons, and strangers, elevates the ordinary to the extraordinary. And it was curated by New Yorker writer-critic Hilton Als.

Here’s the down-low from the gallery’s website:

David Zwirner is pleased to present an exhibition of paintings and drawings by Alice Neel curated by Hilton Als. On view at the gallery’s 525 and 533 West 19th Street spaces, the selection includes works that the artist made during her five decades of living and working in upper Manhattan, first in Spanish (East) Harlem, where she moved in 1938, and, later, the Upper West Side just south of Harlem, where she lived from 1962 until her death in 1984.

Known for her portraits of family, friends, writers, poets, artists, students, singers, salesmen, activists, neighbors, and more, Neel (1900-1984) created forthright, intimate, and, at times, humorous paintings that have both overtly and quietly engaged with political and social issues. In this exhibition, Als brings together a selection of Neel’s portraits of African Americans, Latinos, Asians, and other people of color. Highlighting the innate diversity of Neel’s approach to portraiture, the selection looks at those often left out of the art historical canon and how the artist captured them; as Als writes, “what fascinated her was the breadth of humanity that she encountered.”

Alice Neel, Uptown explores Neel’s interest in the extraordinary diversity of twentieth century New York City and the people amongst whom she lived. The selected portraits include cultural and political figures admired by Neel,..

On our way to a late lunch, a chance stop at the Jack Shainman Gallery introduced us to the cerebral images of Enrique Martinez Celayaart. His deceptively naive, ultimately ambitious art addresses the notions of loss, redemption, nature, and the nature of painting itself.

Celaya is not just an artist, but also a physicist, currently working in painting, sculpture, photography, and writing. His work has been exhibited internationally and is included in the permanent collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The State Hermitage Museum, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, among others.

More on the show entitled “The Gypsy Camp,” the artist’s second solo exhibit with the gallery, (through April 22).

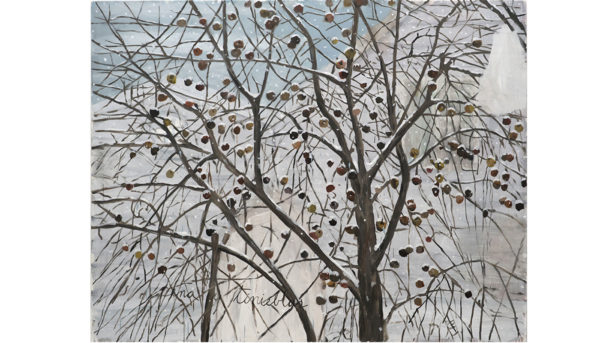

Many of the paintings offer scenes of disrupted journeys or the aftermath of significant episodes: stairs abandoned in fields, snow globes as souvenirs from elsewhere, tattoos that historicize the body, a glass house lost in a cluster of firs, apples frozen and rotting in the tree, and the underlying structure of columns left unfinished. These moments of abandonment and failure also contain the seed of possibility and renewal whose hopefulness echoes the artist’s informed but non-cynical approach to art in general and to painting in particular. In The Folktale (2017), marble stairs are isolated in a grassy clearing; they don’t appear to lead anywhere and a fire burns in the distance, but colorful wildflowers sprout, birds flutter, and sunlight ripples suggesting hope and rebirth.

Nature is a theme throughout Martínez Celaya’s work. Trees recur often as stoic markers of the passage of time. Shelters are also a motif, signaling human presence amidst the rawness of the elements. The Accountant (2016) unites the manmade with its environment. The dwelling is rendered in clear glass or possibly ice, bringing attention to its mechanism of support and to the way it distorts its surroundings, encouraging the viewer to reflect not only on the image, but on the intellectual processes that underlie the work of art and the experience of looking itself.

In this sense, the juxtaposition of sometimes disparate references—for example, roses and rebar—evokes a poetic quality,..

Tia Pol is a tiny, rustic watering hole and a perfect setting for traditional Spanish tapas and daily specials. We consider the restaurant, a popular Chelsea hang, a mandatory stop on any visit to Chelsea.

“Visionaries: Creating a Modern Guggenheim” (through September 6):

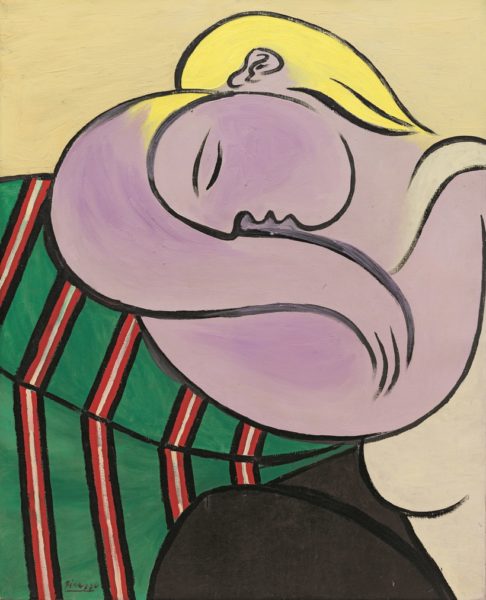

Woman with Yellow Hair, Picasso, courtesy, Guggenheim.

Over 170 modern works of art assembled from an elite fraternity of ground-breaking artists – Alexander Calder, Paul Cézanne, Marc Chagall, Vasily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Fernand Léger, Piet Mondrian, Pablo Picasso, Jackson Pollock, and more. And it succeeds in loudly affirming the great museum’s stature as the major curator of innovative artists and art movements of the late-19th and 20th centuries.

“Visionaries: Creating a Modern Guggenheim” was put together to celebrate 80 years of avant-garde art and the team surrounding Solomon R. Guggenheim, who together cultivated the Guggenheim’s permanent collection. The exhibition will be on view till September 6, 2017.

Here is more on the sprawling show:

Solomon R. Guggenheim’s wholehearted embrace of modern art around the age of 68 was not so dissimilar from his philosophy for succeeding in business. He had never shied away from pioneering, or introducing novel methods, in his prosperous career as a mining industrialist. Having collected art privately since the 1890s, he was ripe for fresh inspiration when he fatefully encountered the German‑born artist Hilla Rebay and the innovations of the contemporary avant-garde. Guggenheim and Rebay were closely aligned from 1929, when they began assembling an art collection grounded in nonobjectivity—a strand of abstraction with spiritual underpinnings—until Solomon’s death 20 years later. This defining focus distinguished the eponymous foundation Guggenheim established in New York in June 1937. Two years later the Museum of Non‑Objective Painting, the forerunner of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, debuted in New York.

The Guggenheim Foundation’s formative collection was shaped through major gifts and purchases from contemporaries who similarly championed radical experimentation in art. These acquisitions include a prized group of Impressionist, Post‑Impressionist, and School of Paris masterworks from Justin K. Thannhauser; the Expressionist inventory of émigré art dealer Karl Nierendorf; inimitable holdings of abstract and Surrealist painting and sculpture from self‑proclaimed “art addict” Peggy Guggenheim, Solomon’s niece; and key modernist examples from the estate of artist and curator Katherine S. Dreier, as well as from Rebay’s estate.

While each collector possessed distinctive motivations, tastes, and art-world relationships, parallels persist. They advocated for arts education and harbored ambitions for establishing cultural institutions, even those who were involved in the commercial side of the art trade. Mutual associations existed with such groundbreaking artists as Alexander Calder, Marcel Duchamp, Paul Klee, Piet Mondrian, and Pablo Picasso. Vasily Kandinsky represents a particularly critical link, and his work forms the nucleus of the Guggenheim Foundation collection today with over 150 examples assembled.

The foresight of these individuals in amassing key examples of the art of their time enables the institution to display the breadth of modernist invention, beginning with the late 19th-century avant-gardists who dispensed with academic genres and techniques in their desire to capture the essence of modern life…

And a link to this wonderful review from The New York Times.

Meredith Nemirov

Posted at 14:15h, 24 AprilJust back from our workshop in Spain! But on the way stopped in NYC and this post brought me back to a wonderful three days visiting museums and galleries. The Biennial was superb! We also saw the Marsden Hartley at the Met Breuer and some good gallery shows. Thanks for the post!