03 Jun TIO Boston: Matisse

Yes, we know. Just post-Mountainfilm, yet another grand slam for Daivd Holbrooke & Co., Telluride is now officially up to its ankles at least in the summer festival season. But there is some unfinished business from our fall trip: for anyone who might be passing through Boston, don’t miss the twin blockbusters at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. We put up a review of the Botticelli show (click here) months ago. That show and “Matisse in the Studio– Objects Inspiring Art,” are up through July 9.

The great French modernist Henri Matisse was not a joiner. In the early 20th century, he led the Fauves (“Wild Beasts) on their colorful, albeit brief, rampage through the the art world, but then segregated himself from the signature movements of modern art. For company, Matisse had his objects, which he described as his “working library,” sources to mine for formal qualities, sculptures and tchotchkes that evoked an emotional response that wound up on canvas as color and pattern – little different from the artist’s live models, which served a similar purpose.

Below is an in-depth, insightful review of that joyous show by our friend Kathleen Stone.

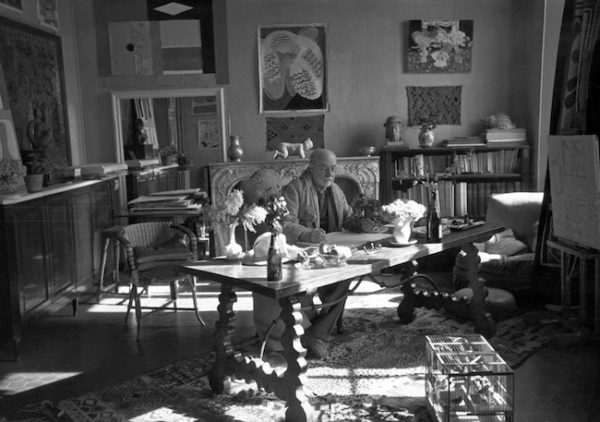

Photograph by Henri Cartier-Bresson (1908-2004) of Matisse with his collection of Kuba cloths and a Samoan tapa on the wall behind him, Villa La Rêve, Vence, 1944*© Henri Cartier Bresson/Magnum Photos *Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

In her book, “Matisse Stories,” A. S. Byatt uses paintings by Henri Matisse as stimulus for the volume’s tales. In one yarn, an uppity painter on the verge of career failure lectures the cleaning lady about why she must not move objects in his studio. He has arranged them just so, he tells her, in order to see the cobalt blue candlestick against the buttercup yellow sauceboat. What’s more, he went into debt to acquire the £ 50 sauceboat because that color was so very important. The cleaning lady listens carefully, keeping her own counsel, and that leads to the final twist of the story which upends assumptions about class and talent. Matisse, who inspired the book, remains a silent presence in the background.

In his own studio, Matisse did in fact surround himself with the colorful objects he used as subject matter for his work, catalysts for his unique artistic vision. That is the driving idea behind the show Matisse in the Studio, a premise the MFA curators effectively mine to trace the evolution of the artist’s work.

The large black-and-white photo (above) shows the artist at a writing table in his studio. Around him is arranged what fueled his work: vases full of flowers on the desk, figurative sculptures and a silver chocolate pot behind him, kube cloth on the wall. These and other artifacts collected from the artist’s studio, most of them now owned by Musée Matisse in Nice, are on display along with a compact but revealing selection of paintings, studies, cut-outs, and sculptures.

Vase of Flowers. Henri Matisse (French, 1869–1954), 1924. Oil on canvas.© 2011 Succession H. Matisse, Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.* Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Matisse is known as a colorist, one of the Fauves, and he uses objects as a point of departure to explore color, volume, and perspective. Two paintings from the early years make the point. In Vase of Flowers from 1924, he places flowers in a green vase in front of a window. The vase itself, shown nearby, is a piece of blown glass from Spain, and it appears again in the 1925 Sofrano Roses at the Window. But the second time, it looks different – more mottled and bluer – putting the lie to any notion of constancy of physical properties. Then there is the matter of angles. In the earlier painting, Matisse defines the walls, window, and floor with right angles and flat color. In the second picture, everything is vertiginous. The viewer’s sight line is squeezed against the wall and the table tips forward; vase and fruit are ready to spill onto the floor. The comparatively muted tones in the first painting are replaced by a brighter palette. Matisse is experimenting here. He anchors his work on the Spanish vase, but then manipulates everything around the object to achieve wildly different results.

Matisse never stopped experimenting. He said his objects were his “working library,” sources to mine for formal qualities and their ability to evoke an emotional response. They came from many cultures, but those from Africa catapulted his art into new directions. As early as 1906, he acquired a Vili figure from the Democratic Republic of Congo (then ruled by Belgium) and prayer rugs and ceramics from Algeria (then under French governance); within two years, he had twenty African figures and masks.

His objects exerted their influence gradually. In a 1907 still life, a Fang reliquary figure appears, but only to play a supporting role. The primary focus of the painting is a French pewter jug; it is as though Matisse is still absorbing what he can from the figure. By 1914, in Still Life with Violet Stockings, he applies a new sense of geometry to a Parisian prostitute with her purple stockings. Given her elongated and flattened chest and the decidedly angular features of her face, the statue’s influence is clear.

Matisse worked differently than his friend and rival Pablo Picasso. Both used African art to shape their innovations, but Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d ‘Avignon (1907), considered the first truly cubist painting, is radical and explosive; Matisse’s evolution was gentler. He never truly embraced cubism, but used color and pattern like no one else.

The late canvas Interior with Egyptian Curtain (1948) is stunning: pink table with yellow fruits, window frame full of green and blue palm fronds, red, green and black curtain hanging in front of the glass. The Egyptian curtain from the painting and several haiti (pierced and appliquéd cotton hangings) are on display, and we can see how their intricate patterns intoxicated Matisse. He used textiles as background in The Moorish Screen (1921), but also allowed them to take over the entire picture plane, rendering background and foreground a distinction without a difference, as with Interior with Egyptian Curtain. Pattern and color are the primary compositional elements, more important than the quasi-realistic appearance of what is ostensibly the subject of the painting.To understand Matisse as a colorist, don’t miss Still Life with Heron Studies…

More about Kathleen Stone:

Kathleen Stone

Kathleen Stone lives in Boston and now writes critical reviews for The Arts Fuse. She co-hosts a literary salon known as Booklab, plays jazz piano, and is at work on several major projects. Kathleen holds graduate degrees from the Bennington Writing Seminars and Boston University School of Law. Her blog can be found here.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.