02 Mar Slate Gray March: Women from The Faraway!

For the month of March Slate Gray Telluride has mounted a group show titled “Women from the Faraway. The artists whose work is on display all hail from New Mexico, once the adopted home of Georgia O’Keefe, who described her vision of the stark Mexican desert as “The Faraway Nearby.”

The show officially opens with Telluride Arts First Thursday Art Walk. For other participating venues, go here.

Divine Intervention, Bette Ridgeway

Georgia O’Keefe & “Women from the Faraway”:

fig. 78: Alfred Stieglitz

Legendary photographer and gallerist Albert Stieglitz was an influencer before there were influencers. He certainly knew a good thing when he saw it. Sent the work of a beautiful young graphic designer and fine artist by one of her former classmates, Stieglitz was gobsmacked: he had to hang the images on the walls of his avant-garde Gallery 291, (at 291 Fifth Avenue), also the staging ground for an elite fraternity of burgeoning art world alpha males, among them, Rodin, Matisse, Picasso, Duchamp, and Brancusi.

Back then, Stieglitz is alleged to have declared “Finally a woman on paper,” words that morphed into a mixed blessing because they opened the door to a highly sexualized interpretation – however true – of Georgia O’Keeffe’s work (particularly her florals). Nevertheless a star was born.

Later, reputation and myth secured as aa pioneering painter and feminist icon, O’Keefe rebuked the claim, declaring it said more about the viewer than her artistic intentions. But methinks the lady protested too much – and/or those protests were about something else, about the idea, or a variation on the theme, “She threw well – for a girl.” “Ran well – for a girl.” In short, O’Keeffe’s objection to anatomical interpretations of her work feels like nothing more than her taking exception to Stieglitz’s contention that art made by a man was naturally, inherently different (and better) than art made by a woman. Best guess is that in O’Keefe’s mind, good or bad, art was art. Gender did not, ahem, enter the picture.

Gender does, however, enter the pictures on the wall of the Slate Gray Gallery throughout the month of March – if only in that the group show is titled “Women from the Faraway,” a tribute to O’Keefe, who lovingly described the desert of New Mexico as “The Faraway Nearby.”

And, as the first female American modernist artist, Georgia O’Keefe is clearly the eminence grise of the sorority featured at Slate Gray, where being seen through a gendered lens is not a bad thing. “Women from the Faraway” features the work of Martha Rea Baker, Alexandra Eldridge, Ali Lauder, Bette Ridgeway, Kathrine Tatum, and Amy Van Winkle.

The show officially opens on Thursday, March 4, with Telluride Arts’ March Art Walk.

Women from the Faraway:

Bette Ridgeway, abstract painter of color, space and time and winner of Michelangelo International Prize 2021, first up because she is also the newest addition to the Slate Gray stable:

An Aria for RBG, Bette Ridgeway

The Michelangelo International Prize is awarded to artists worldwide who have made important contributions to the art of painting, architecture and sculpture, as well as art theory. One of the most prestigious art awards presented in Florence, Italy, it is also highly recognized internationally by the academic world. For her large-scale, luminous, poured canvases that push the boundaries of light, color and design, in January 2021, painter Bette Ridgeway received the coveted tribute.

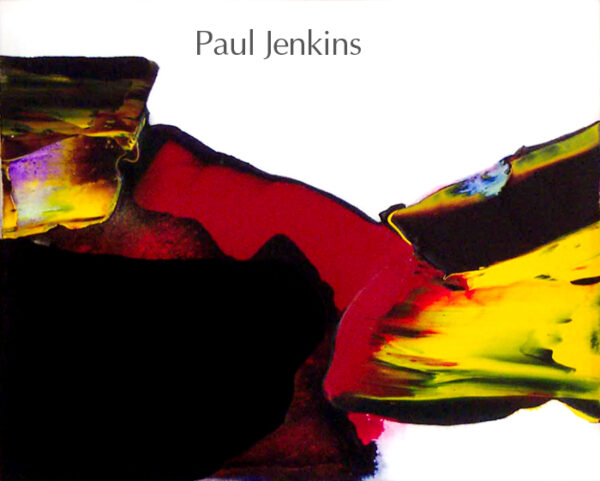

Honoring Ridgeway’s work, Dr. Salvatore Russo Rome – he curated the Michelangelo Prize this year – described the artist as “The true heir of Paul Jenkins’ paintings as a ritual. The spiritual in art, which takes shape through a ‘slowed down’ process based on the indistinguishable union between time – space – color. (In Ridgeway’s hands) the canvas becomes a diary in which to write down your emotions, your feelings and, above all, where you can freely express your ideas.”

Early on, the American Master Paul Jenkins adopted a tactile, chance-driven method of working, dribbling the medium Jackson Pollock-like, onto loose canvasses. His paint rolled, pooled and bled onto surfaces that magically evolved into psychedelic landscapes.

Jenkins’s career began in the 1950s, in the wake of the Abstract Expressionists, but was spurred on by Color Field painting that followed. Like Jenkins, Ridgeway’s eye-popping work lives and breathes at the nexus of those two schools of American art, one action-oriented; the other more cerebral and “pure” or art for art’s sake. In the hands of masters, the work is sensuous enough to be PG-rated.

Ridgeway once described her first encounter with the paintings of the man who would become her mentor:

“I walked into Gimpel & Weitzenhoffer Gallery in 1978 in New York, the entire space was filled with enormous canvas paintings by Paul Jenkins. It completely stunned me. It was a ‘color storm’ of the most incredibly powerful poured-paintings in primary colors. My body went numb and I wept. It was a soul-stirring experience that took my breath away. As I studied each painting, I had (what I now know) was an out-of-body experience. It was the entirety of the exhibition that filled my heart, mind and spirit.”

Ridgeway has spent four decades (and counting) developing her signature technique, which she describes simply as “layering light.” As is the case with Jenkins’ oeuvre, Ridgeway’s images suggests a pas de deux between luminous colors (created by the artist herself in a blender) and rhythmic movement.

Transformation, Bette Ridgeway

“Devoted to the powerful autonomy and perceptual properties of color; New Mexico-based artist Bette Ridgeway has spent her artistic career developing a radiant body of abstractions that place her at the forefront of the second-generation of Abstract Expressionists,” said Laurence F. Jonson of the AACR Gallery.

Jenkins himself once described Ridgeway’s work as “controlled chaos.”

Initially trained as a watercolorist, the artist’s love affair with water media began as a youngster growing up in the Adirondack Mountains in upstate New York, surrounded by natural beauty.

Ridgeway went on travel the globe, studying, painting, teaching and exhibiting her work, while embracing the customs and colors of the diverse cultures of Africa, Australia, Europe, Asia, Central and South America.

Her formal art studies at Russell Sage College, New York School of Interior Design and the Art Students League gave the artist the basic tools in the use of materials and technique.

Her celebrated signature style, however, was a long time coming, artistic foundations in watercolor, line drawing, graphic design, and oils ultimately giving way to acrylics, which the artist found to be more versatile for layering.

A Time Before Thought, Bette Ridgeway

“My career began in the sweatshop of Reuben Donnelley Advertising as a young graphic artist and, over many decades, has taken me to the outdoor marketplaces in Tananarive, Madagascar; the urban dynamism of Santiago, Chile, and the modern youthful capital of Australia in New South Wales…Canberra. And many stops in between,” explained the artist.

Bette Ridgeway has exhibited her work globally in over 80 museums, universities and galleries, including: Palais Royale, Paris; Embassy of Madagascar; Kobayashi Gallery, Tokyo; and London Art Biennale.

Among the prestigious awards she has garnered are the aforementioned Michelangelo International Prize; Top 60 Contemporary Masters; Leonardo DaVinci Prize, Rome; Sandro Botticelli Prize, Museum, Florence; and the Oxford University Alumni Prize at the Chianciano Art Museum, Tuscany.

In addition to countless important private collections, Mayo Clinic, University of Northwestern, and Federal Reserve Bank are amongst Ridgeway’s permanent public placements.

Since 1996 Ridgeway has maintained an art practice in Santa Fe, NM, where she claims the high desert light fuels her spirit – shades of O’Keefe.

Martha Rea Baker:

Canyonlands Both

Like Ridgeway, Martha Rae Baker is an action painter or an Abstract Expressionist 2.0, in the lineage of the fraternity formed in New York after WWII which included now iconic artists like Pollack, deKooning, Kline, Still and Jenkins. However, the old boy’s club tended to create from macho pathos. Baker makes her distinctive marks from a place of pure joy, working as she does from a light-filled studio in the footprint of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains of Santa Fe, drawing inspiration from nature, poetry, and music.

Baker works primarily in encaustic (melted beeswax fused with heat), but also in oil/cold wax and acrylic such as in the images on display at Slate Gray…

Portal V

For more on the artist, go here.

Alexandra Eldridge:

Twin Souls, Alexandra Eldridge

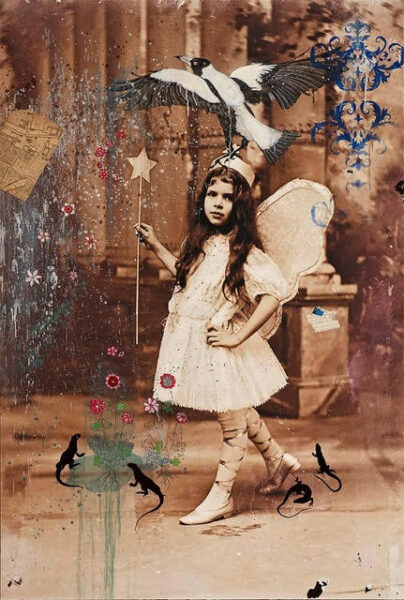

William Blake (November 28, 1757 – August 12, 1827) was an English poet, painter and printmaker, raised in a church that believed in the “Doctrine of Correspondence,” which holds that everything material mirrors something spiritual.

Carl Jung believed in the “complex,” or emotionally charged associations. He founded analytical psychology and advanced the idea of introvert and extrovert personalities, archetypes, and the power of the unconscious…

Or, in this context, the place where Alexandra Eldridge’s deeply poetic art emerges:

“My paintings come from a place where contradictions are allowed, paradox reigns, and reason is abandoned. My search is for the inherent radiance in all things . . . the extraordinary in the ordinary.

“The process of painting parallels the movement of psyche, helping me to understand the world as a deeper reality. The rich-soul experiences of my life become tangible. Each painting is a small acknowledgment of the inner life that can, perhaps, reveal its own share of soul, and that share of soul may connect to someone else’s share of soul. Then, perhaps, beauty may be granted.”

The Young Sorceress, Alexandra Eldridge

For more on the artist, go here.

Ali Launer:

Native Silver Blesbok, Ali Launer

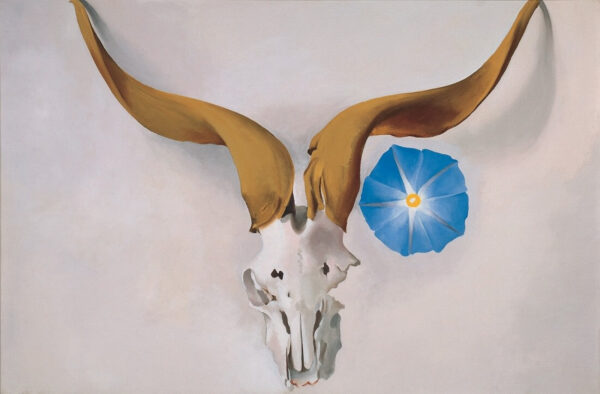

Captivated by the culture and colorful desertscapes of New Mexico, Georgia O’Keefe’s celebrated paintings pay tribute to the region’s flora and fauna, among them, “Rams Head Blue Morning Glory.”

Rams Head Blue Morning Glory by Georgia O’Keefe

“I found I could say things with color and shapes that I couldn’t say any other way – things I had no words for,” the celebrated artist once-upon-a-time-ago explained.

Fast forward about 100 years (from the time Albert Stieglitz discovered O’Keefe in 1916), inspired by O’Keefe, another denizen of New Mexico has also memorializes rams’ heads – and those of other critters like bison, bull, African impala, oryx, and kudu.

In a unique spin on taxidermy, the graceful shape of each animal’s head serves as a 3D, shaped canvas that houses the intricate details of Ali Launer’s art…

White Druzy Longhorn, Ali Launer

For more on the artist, go here.

Kathryn Vinson Tatum:

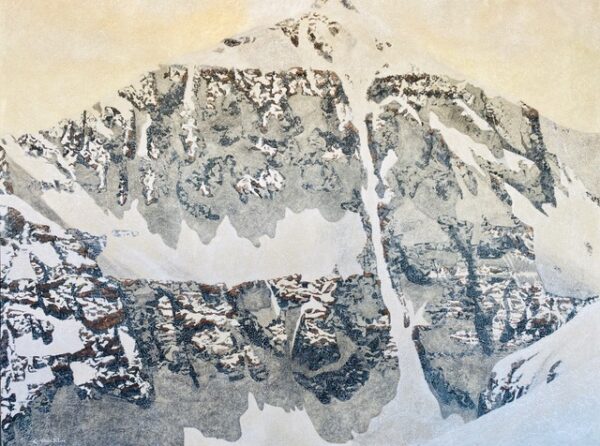

Meru, Kathryn Tatum

Kathryn Vinson Tatum is a painter of action, capturing the the Rockies of Telluride and Taos, New Mexico, her two homes, in paintings that celebrate the emotional impact of being on top of the world above tree line. In short, “off-piste” describes Tatum both as an artist and as a skier who regularly enjoys shooting the moon.

Vinson Tatum’s journey from graphic designer to rock stars to fine art painter in the Rockies began in rural New Jersey…

In 2006, Tatum and her husband began spending six months a year at their ranch in Taos. In 2011, they moved to the town of Ranchos De Taos to be closer to the highly established Taos art scene (while holding onto the ranch).

“That was where my painting techniques developed into a synthesis of Chinese processes and philosophies and Western art techniques and materials. By combining rice paper, charcoal, Chinese ink and brush techniques with acrylic paints and wax, my mixed-media synthesis finally reached its fullest expression…”

San Joaquin Couloir, Kathryn Tatum

For more on the artist, go here.

Amy Van Winkle:

Evermore, Amy Van Winkle

Everything old is new again in the work of artist Amy Van Winkle.

Encaustic painting, the name derived from the Greek word enkaustikos meaning “burnt in,” was one of the the principal styles of painting in the ancient world, dating back at least two millennia. The technique involves using heated beeswax to which colored pigments are added. The liquid or paste is then applied to a surface — usually prepared wood, though canvas and other materials are often used.

Eliminating figure and ground in favor of color and form, Van Winkle’s encaustics force a focus on paint, surface, texture, and gesture, creating abstract images that are effectively “soulscapes,” both revealing and concealing the artist’s inner world and life experiences. Space, time, and transition are common themes in her art.

Today Van Winkle lives full-time in Santa Fe with her husband Mike, son Declan, and two dogs, Seamus and Oliver. Her work is featured in both private and corporate collections.

Living In Twilight, Amy Van Winkle

For more on the artist, go here.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.