02 Jun Telluride Arts, June Art Walk: Highlights

Telluride Arts’ First Thursday Art Walk is a festive celebration of the art scene in downtown Telluride for art lovers, community and friends. Participating venues host receptions to introduce new exhibits.

The first Art Walk of the summer 2019 season takes place Thursday, June 6. 5 –8 p.m.

Go to Telluride Arts to read about all of the participating galleries.

Below are a few June Art Walk highlights (in alphabetical order): Andrew Brown at Slate Gray Gallery; Jim Herrington at Telluride Arts HQ; Nelson Parrish and David Benjamin Sherry at the Telluride Gallery of Fine Arts; and Faviana Rodriquez at Gallery 81435.

ANDREW BROWN AT SLATE GRAY:

The dominant movement in American painting in the late-1940s and 1950s, Abstract Expressionism was the first major development art to lead rather than follow European influences. AbEx so energized the American art scene post WWII that New York wound up replacing Paris as the world capital of contemporary art. Strictly speaking, Action Painting translates to a dynamic, impulsive attack on a surface in which paint is applied with gestural movements – scratching, dribbling, splashing – with little or no preconceived idea of what the end result will look like.

It is painting in the zone during which time an artist’s creative interaction with his materials is just as important as the finished product.

The means justifying the ends.

Welcome to the world of Andrew Brown, whose show “Chaos and Order” is up at Beth Mclaughlin’s Slate Gray Gallery through June.

A Southwest Colorado native, Andrew is the son of renowned landscape artist Gordon Brown. Father and son share a studio, a converted barn, down the road apiece in Norwood.

So yes, the apple does not fall very far from the tree.

But while Brown père’s work depicting an idealized, somewhat (or entirely) abstracted, natural world, landscapes, and seascapes – on display across the street from Slate Gray at the Telluride Gallery of Fine Art – feels lyrical and atmospheric, young Brown’s art is raw and intense, reflecting the turbulence of hungry youth.

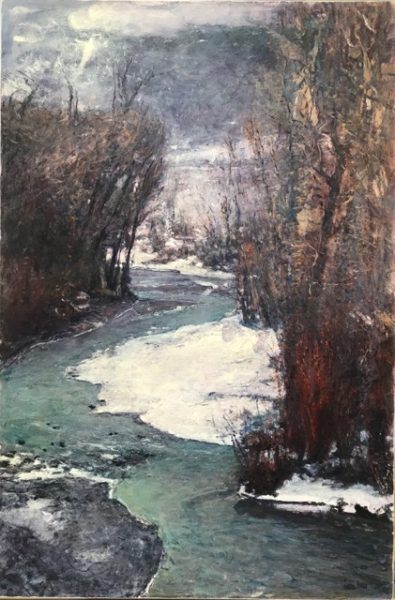

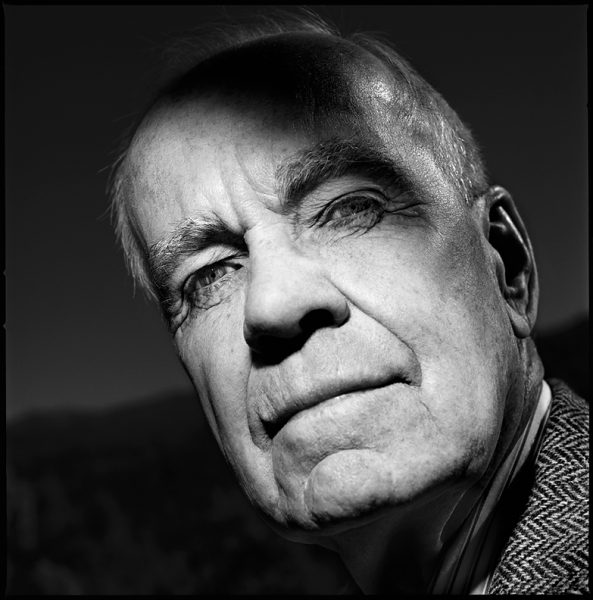

Image, Gordon Brown of the Telluride Gallery.

Abstraction, Andrew’s father Gordon Brown.

While both artists share is a desire to capture a mood, not the thing itself, Andrew is still testing and pushing his limits; Gordon has already arrived. He can kick back a bit and muse.

At this point in his young life, the son of a quiet, lyrical painter is making lots of noise: building up and tearing down layers of rich pigment and cold wax, in his work, glazing, heating, melting, scratching, scraping until he finds what he was after.

In other words, the very physical young painter Andrew Brown is a true heir of the Abstract Expressionists or “Action Painters” of yore.

“My dad advised me not to become a professional painter, but I was already drawing and painting in middle school and high school. Then one summer I went out to California, started painting oceanscapes and loved it. For me, painting is a moving meditation and I work off impulse. Lots of stimulants trigger me: a walk at the lake; picking up a new pigment; a podcast. I am into abstraction because not having to recreate a concrete subject – like a body of water or a tree – helps keep me out of my head I can remain detached and involved all at once. Then, when I first start to paint, the process is unorganized and random. It’s messy, and I enjoy that. It excites me to bring some kind of order to chaos, to create something meaningful out of a blob of paint. But my dad taught me realism and abstraction really come down to the same things: shape, line, color, composition, edges.”

Lots going on under Andrew Brown’s roiling, vivid surfaces as he projects a feeling onto a canvas or board and infuses it with light and color.

JIM HERRINGTON, TELLURIDE ARTS HQ:

Once upon a time, photography was considered too much of a democratic medium (read, anyone with a point-and-shoot could do it), too fast, slick and facile to be considered fine art. It was also regarded as too indecently young to be considered museum-worthy with a history going back only as far as 1839.

But those dusty ideas changed in the late ‘90s when revered institutions like New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art began displaying its collection of fine art photography,(originally stashed in the corner of a storage room in the print department), and works by major photographers began to command top dollar at auctions.

Fast forward to the present day and those same august institutions are still caught scratching their heads, this time about the direction of photography in an era when cameras and lenses are optional, even quaint, and variations on theme unending.

But, as artist Nan Goldin famously said: “Cameras don’t take great pictures. Artists take great pictures.”

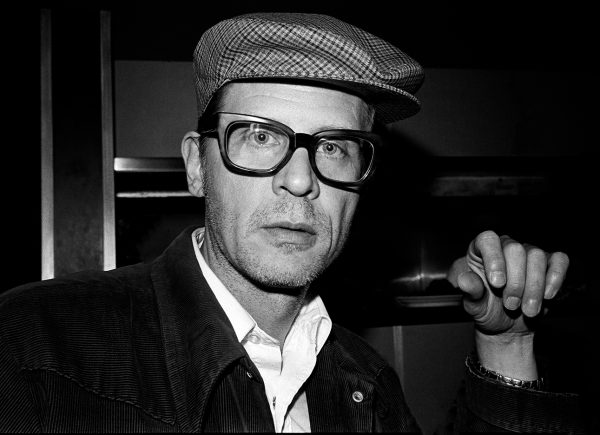

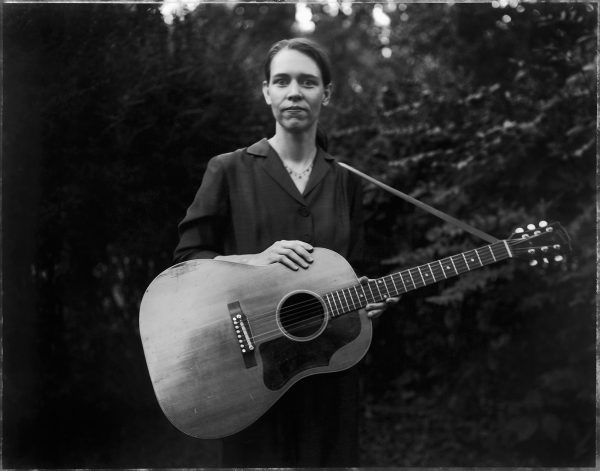

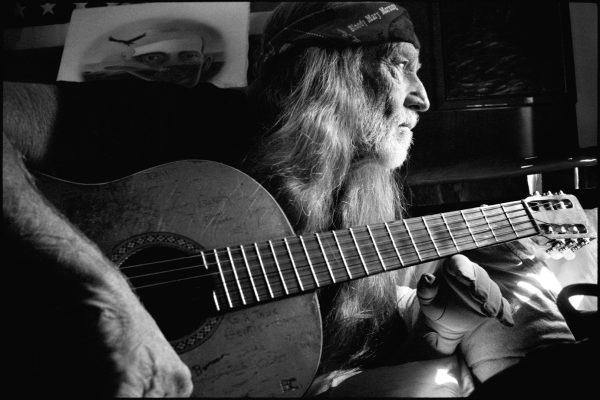

Jim Herrington is one of those great artist-photographers who, for decades now, has used his lens (and yes, conventional cameras) to mine for emotional depth – always striking pay dirt – while also pursuing his other love: climbing.

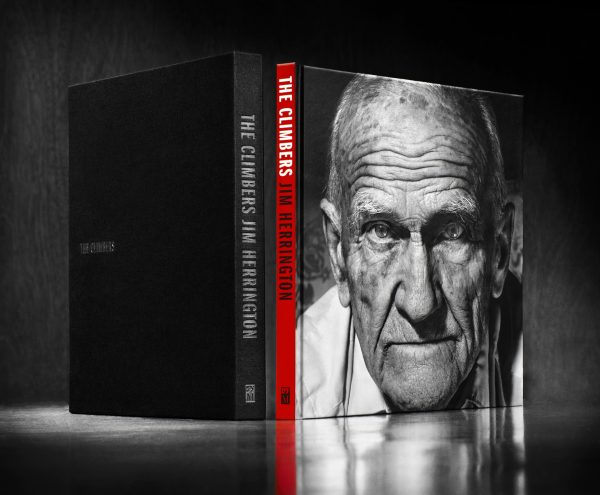

The latest work of the celebrated photographer, “The Climbers,” marries Herrington’s twin passions. Images from the book are on display at Telluride Arts’ HQ (across the street from the Telluride Library) through June.

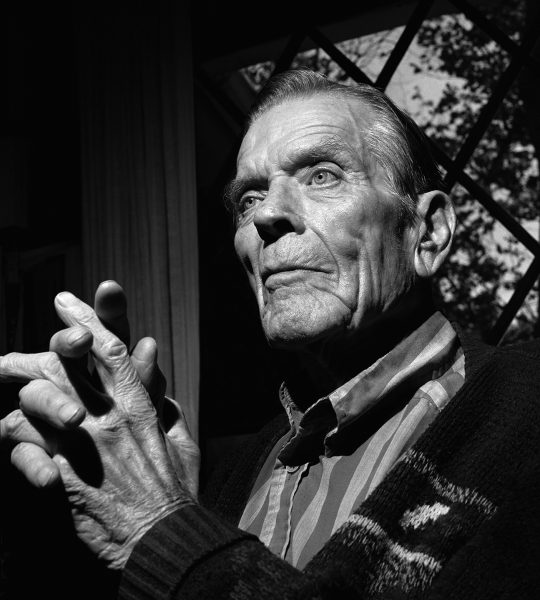

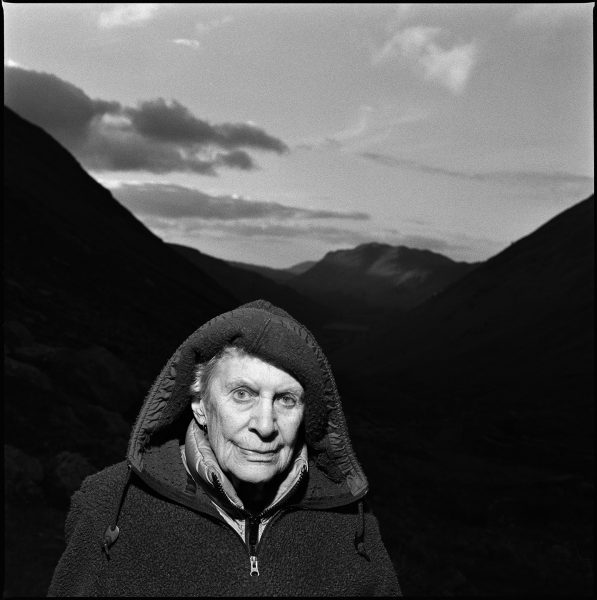

“The Climbers” features faces from the golden age of the sport, defined by Herrington as “those who were vertically active between the 1920s and 1970s.”

In other words, former legends who might otherwise have been overlooked in favor the youth who tend to dominate in all adventure sports. But it is those people, Herrington’s people, who long ago discovered what was possible and how far things could be pushed – all the way uphill.

How did the project get jump-started?

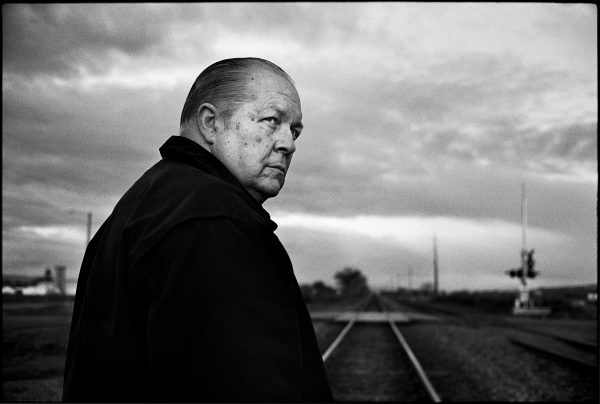

Inspired by the Sierra Nevada routes he had been climbing for more than a decade while living in Los Angeles, Herrington set out in the 1990s to photograph the range’s pioneering climbers, among them, Glen Dawson and Jules Eichorn, octogenarians when he finally caught up with them. He then went on to tour the globe from California to Cumbria to Kathmandu, 10 countries in all, to capture the faces of other world-renowned alpinists. Published in October 2017, “The Climbers” is the result of Herrington’s 20-year quest.

The large format coffee table book turned out to be a 192-page tribute to the discipline’s greatest hits, rugged individualists, men and women alike, who used primitive gear along with their considerable wits, talent, and fortitude to tackle unscaled peaks around the world. The 60 openly honest, no frills, black-and-white portraits of 60 climbers includes the likes of Royal Robbins, Reinhold Messner, Yvon Chouinard and Riccardo Cassin. The forward is by none other than Alex Honnold, the famous subject of “Free Solo,” which won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.

Shot on analog film, “The Climbers” allows us to study the faces of the men and women who ascended bold, visionary lines, often in remote regions, far from the media spotlight. Herrington’s portraits plumb their faces to reveal, through their eyes, the utter humanity of obsession, determination, intellect, and, at times, frailty.

“…It is as if Richard Avedon had photographed mountaineers rather than movie stars, minus the props and gimmicks,” David Roberts.

“Herrington looks for the meaning of the koan in the faces of the climbers themselves, through their stony gazes and crenellated skin…it’s mesmerizing stuff,” Amazon’s Omnivoracious book blog.

“20 years of gorgeous photos by Mr. Herrington. A gift of beauty and grit,” The Wall Street Journal.

“…Herrington more than achieves his aims: to both inspire and provoke his readers to reflect on how we’re transacting our own lives, which end all too quickly. The stills—all black and white, all starkly honest—speak for themselves,” Outside Magazine..

Jim Herrington, more:

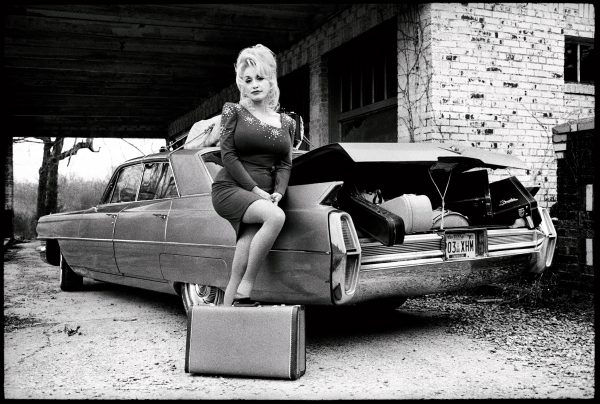

Jim Herrington is a photographer whose portraits of celebrities including Benny Goodman, Willie Nelson, The Rolling Stones, Cormac McCarthy, Morgan Freeman and Dolly Parton have appeared on the pages of Vanity Fair, Rolling Stone, Esquire, GQ, Outside and The New York Times, as well as on scores of album covers for more than three decades. He also photographed international ad campaigns for clients such as Thule, Trek Bikes, Gibson Guitars and Wild Turkey Bourbon.

Herrington co-produced the Jerry Lee Lewis episode for the HBO/Cinemax series “Mike Judge Presents: Tales from the Tour Bus” that premiered September 2017.

Herrington’s photography has been exhibited in solo and group gallery shows in New York City, Los Angeles, Washington DC, Nashville, Milwaukee and Charlotte, and is in numerous private collections.

He now divides his time between New York City, Owens Valley, CA and Southern Europe.

The following two tabs change content below.

NELSON PARRISH & DAVID B. SHERRY, TELLURIDE GALLERY OF FINE ARTS:

Left to right, Nelson Parrish & David Benjamin Sherry standing in front a work by Sherry at the Telluride Gallery of Fine Art.

Nelson Parrish:

The word “flitch: refers to a plank of timber, cut lengthways from a tree trunk. Flitch beams consist of a steel plate sandwiched between two solid timber members and bolted together. Further alternating layers of timber and steel can be used as required to increase the strength of the beam.

Flitches, misogi and photography as a medium for capturing slices of life all come into play in the art of Nelson Parrish.

About six years ago, and for the second time in two years, Atlanta Hawks guard Kyle Korver and a group of friends got together in chilly waters along the coast of Santa Cruz Island about 30 miles south of Santa Barbara to perform a Sisyphean ritual that involves gnar exercises like underwater rock running or paddle boarding for miles and miles across the Santa Barbara Channel.

They were practicing misogi, a secret, punishing ritual executed by some followers of Shintoism involving cold water immersion therapy. The benefits have been corroborated by modern science – and by super-shooter Korver’s winning ways.

“…(That day) there (was) Marcus Elliott, 48, the mastermind behind this sufferfest, a Harvard-trained sports scientist who works with pro athletes and enjoys all-night jogs; Deyl Kearin, 34, a mellow real estate investor who ran 150 miles across the Sahara in 2012 and looks like he could be Laird Hamilton’s clean-cut younger bro; and Nelson Parrish, 35, a sturdy, Alaska-bred, former junior Olympic skier whose artwork, collected by John Legend and Rob Lowe, depicts “the color of speed…,” wrote Outside magazine about the event.

One of Nelson Parrish’s breathtaking flitches, strong and delicate at once.

The term “Action Painting” is often used as a synonym for the work of a loose confederacy of artists known as the Abstract Expressionists, a lineage that became the dominant force in American painting by the end of the 1950s. As a group, AbExers were not unified by much except for the fact that what drove them all – from Mark Rothko to Clyfford Still, Robert Motherwell and Jackson Pollack – was an unbridled sense of freedom of expression that marked post-WWII America.

However, the term “action painter” takes on a whole new, far less subtle meaning when applied to artist Nelson Parrish, who has lived his life in constant motion and has no plans to quit now, especially not since his career has gained serious momentum.

Parrish grew up in Alaska where he spent his youth careening down slopes, pedaling over ridge lines, swimming across lakes, hiking into the backcountry – and years later, practicing the aforementioned misogi, which he once described as “a mental and spiritual challenges wrapped in a physical package.”

That description equally applies to Parrish’s art, generally speaking his “totems,” the artist’s term for works that are flashes of color – or how we see a world in motion – captured in planed wooden planks wrapped in layers of semi-transparent and color-infused bio-resin. These totems, fusions of painting and sculpture, are very physical abstractions that capture and freeze many of the breakneck moments in the artist’s life when his perceptions of the world are naturally intensified.

No matter what form they take, all of Parrish’s powerful work uses color and light and intense interaction with his surroundings to bring focus and clarity to his unique artistic expression, so that all of his art evokes the same sense of elation in his viewers Parrish feels in motion when in the outside in the physical world – or inside in his studio.

It could be said that Parrish’s sculpture-like forms encapsulate the pure joy of living fully in each and every moment.

They are all about challenging himself – and us – in unexpected ways to push the envelope: physical, mental and emotional.

Action “painting” writ large.

David Benjamin Sherry:

“My job as an artist is to make sense of what’s happening around me, by any means necessary,” David Benjamin Sherry.

Talk about in your face.

Winter Morning Fog, Bridalveil Falls, Yosemite, California, 2013, courtesy Telluride Gallery.

As spectacularly colorful as a box of big, fat lollipops, the large-format photographs of artist David Benjamin Sherry could be described as eye candy.

Just a whole lot more beautiful, impossibly bright and infused as they are with ethereal hues.

Images of the monoliths of Yosemite Valley, the pristine High Sierra, the dramatic cliff lines of Big Sur, and the majestic peaks of the Rockies are synonymous with the rugged beauty that is the American West. As a result, these wondrous places have inspired countless painters (think Bierstadt) and photographers (think Ansel Adams) who helped argue for the sacredness of wilderness.

Sherry once said that examining older photographs and reading the placards at National Parks indicating where specific sites had been altered due to climate change shocked him. Then, in an interview with Slate, he talked about a day he was listening to a radio interview while driving and was moved by what Elizabeth Kolbert of The New Yorker had to say, then subsequently wrote in her book, “The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History.” Kolbert’s observations hit like a gut punch and became a driving force behind Sherry’s dramatic reaction to the world around him.

His psychedelic landscapes, vivid combinations of reality and fantasy suffused with surrealistic detail, are, then, spectacular records of environmental disasters-in-process due to climate change, which means his images are a form of protest art, an edgy remix of past efforts to use art to raise consciousness and effect socio-cultural change.

It all began about a decade ago when David Benjamin Sherry started traveling through the American West. Though he was born in 1981 in upstate New York near the Catskill Mountains, once he began photographing the terrain on the other side of the country, Sherry said he felt drawn to the classic landscapes around the national parks, as well as to the work of Ansel Adams and Edward Weston.

In the history of American conservation, few have worked as long and as effectively to preserve wilderness and to articulate the “wilderness idea” as Ansel Adams, who famously described wilderness as “a mystique: a valid, intangible, non-materialistic experience.”

So like his mentors, Sherry is a crusader.

Desert Hills, Death Valley, California, 2013, courtesy, Telluride Gallery.

But like Weston, who along with Adams believed that the artist should stand above and beyond the noise of current events, Sherry’s work also focuses our gaze (and hearts) on the more enduring and transcendent qualities of his muse, Mother Nature.

As compelling and awesome as Sherry’s color-saturated, monochromatic, topographical landscapes are, his work is also surprising because they are throwbacks, analog, not digital, prints shot with a large format camera at f/64 and then created the old-fashioned way from shooting film to printing in a darkroom. The result is art that is much warmer than digital prints which tends to feel at one cool remove from the maker.

“…I love the instability of analog photography, the alchemical qualities of it, the dangers of it, the history of it, the mysticism tied to it, the exclusivity of it, the isolation of it, and the complete embodiment of it—meaning that once inside of a completely darkened room, using a small amount of light to expose a piece of paper, I actually become the internal workings of a sort of camera. While in the darkroom, I control the enlarger and the paper surface. My body becomes an integral part of the working machine. Through this process, I embody my print and become a working part of the camera,” Sherry told Aperture.

David Benjamin Sherry, more:

David Benjamin Sherry is an American photographer based in Los Angeles. Sherry’s work consists primarily of large format film photography, focusing on landscape and portraiture, and has been exhibited in New York, Los Angeles, London, Berlin, Aspen and Moscow.

Now known an environmentalist for the common man (with uncommon talent) David Benjamin Sherry received his BFA in Photography from Rhode Island School of Design in 2003 and his MFA in Photography from Yale University.

His work has been featured in many prominent international publications, from Artforum and Aperture Magazine to The New York Times, and many others. In September 2014, his work was featured on the cover of The New York Times Magazine.

His exhibition at MOMA in NY and subsequent shows at the Aspen Art Museum, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow, Saatchi Gallery in London, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, ICP International Center for Photography in New York and Massachusetts Art Museum have cemented his reputation in both art and photography.

FAVIANNA RODRIQUEZ, TELLURIDE ARTS’ GALLERY 81435:

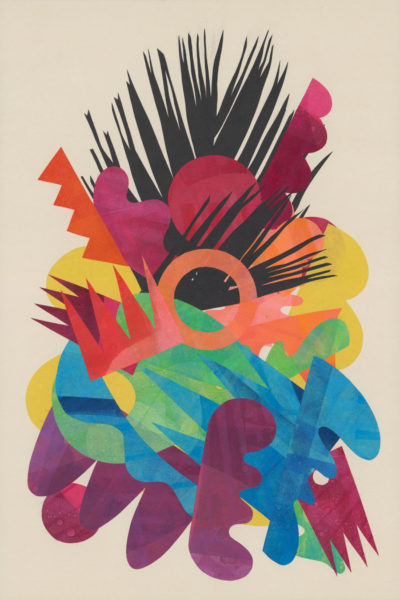

Favianna Rodriguez is an interdisciplinary artist, cultural strategist, and social justice activist based in Oakland, California. Her art and praxis address migration, economic inequality, gender justice, sexual freedom, and ecology.

Her practice boldly reshapes the myths, ideas, and cultural practices of the present, while confronting the wounds of the past.

Rodriquez’s signature mark-making embodies the perspective of a first-generation American Latinx artist with Afro-Latinx roots who grew up in working-class Oakland, California during the birth of the internet, and in the midst of an era of anti-immigrant hate and the war on drugs.

As part of her practice, Rodriquez leads art interventions around the United States. Her artistic modalities include social practice, visual art, arts advocacy, and institution building. She also collaborates deeply with social movements to co-create visual narratives and cultural strategies that are resilient and transformative.

In addition to her expansive studio practices, Rodriquez is Executive Director of CultureStrike, a national arts organization that empowers artists to dream big, disrupt the status quo, and envision a truly just world rooted in shared humanity.

In 2016, Favianna Rodriquez received the Robert Rauschenberg Artist as Activist Fellowship for her work around immigrant detention and mass incarceration. In 2017, she was awarded an Atlantic Fellowship for Racial Equity for her work around racial justice and climate change. In 2018, she began organizing with artists in the entertainment industry through 5050by2020.com, an initiative launched by Jill Soloway to build intersectional artist power.

“Plants and trees give us the oxygen we breathe every day. This new body of work is about my transformative and healing relationship to plants, nature, and plant medicine. As an artist-activist engaged in organizing communities around climate justice, I believe we must tell different stories about our human relationship to nature so that we may realign with our mother earth and reimagine solutions to the climate crisis. Our current social, political and economic system is built upon the exploitation and abuse of the planet, animals, and people – mostly people of color and migrants at the global level. People of color disproportionately suffer the impacts of climate chaos, and therefore, it’s imperative that we tell our stories about how environmental catastrophe affects us, as well as how nature holds the knowledge that can help move us forward. We must urgently build an alternative system of energy, but in order to do so, we must first change how we view nature and the world around us. In creating this new body of work, I sought to cultivate a deeper relationship to plants and nature as a key pathway to personal and collective liberation. I began caring for an urban garden for the first time, and nourishing plants in my home for the first time. I tried plant medicines for the first time and was connected to a portal of deep ecological intelligence, which taught me how to see nature differently. These works are a product of this transformative practice within myself.”

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.