18 Sep UC Health: Coronavirus Mutations Not (Necessarily) Cause for Alarm

We curated this excellent article by Ted Neff from UCHealth Today. The subject: Coronavirus mutations not (necessarily) cause for alarm. “Recent mutation, one of many, may increase infectiousness, but doesn’t seem to increase COVID-19 severity,” Neff explains.

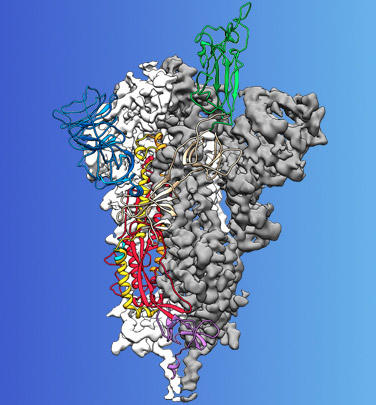

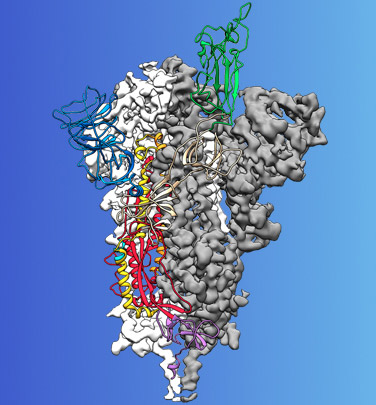

A computer model of the spike protein of the SARS-CoV-2. A recently identified mutation subtly changed the spike’s shape and, probably, made the coronavirus more contagious. Image courtesy of NIH and UT Austin/McClellan Lab.

Organisms mutate. That’s often a good thing. If it weren’t for mutations, we might all still be single-celled organisms clinging to hydrothermal vents in the ocean’s black depths.

Mutations – random, inevitable changes to life’s genomic code – don’t always turn slime into Shakespeare, though. Viruses mutate also.

SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind the COVID-19 pandemic, is no exception. The coronavirus’s RNA genome consists of about 30,000 base pairs. Since Chinese scientists first decoded the virus’s genetic code in December, it has accumulated an average of one or two random mutations a month. One in particular, called D614G, may well have boosted disease’s infectiousness.

That particular coronavirus mutation has raised questions about the future of the coronavirus – and, by extension, the possible impact on the civilization the virus has attacked.

Viral mutations come and gone

Viral mutations have been well documented. The 1918 Spanish flu pandemic was caused by a virus that mutated (probably from waterfowl who weren’t bothered by it) to infect humans. That virus, H1N1, hung around in people until 1957, when some combination of mutations and increasing immunity caused it to fade from our species. In 1977, a mutated version of H1N1 emerged again and jumped from pigs to humans in China. The same thing happened in 2009, causing the H1N1 swine flu outbreak. That H1N1 strain still circulates as a seasonal flu virus whose mutations have now changed fully 15 percent of the original Spanish flu genome. The good news: in general, H1N1 has become less virulent with time.

That’s not by chance. If you’re a virus with the sole goal of proliferating as widely as possible, mutating to cause a mellower infection makes sense. (Even HIV may be evolving into a less-dangerous form.)…

Continue reading here to learn the good and bad news about coronavirus mutations and more…

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.